A radical new way of thinking about the relationship between Creation and the Atonement leads James Alison to consider a framework for the Eucharist in which ‘the Creator and Redeemer is engaged in an act of daring’.

In her astounding book, The Revelation of Jesus Christ,[1] Margaret Barker offers the most plausible reading of the Book of Revelation that I know. She also enables us shift our paradigm for understanding Redemption. In this article I am going to borrow freely from Barker’s insights to bring out the nature of that paradigm shift as it affects our participation in the Eucharist, to see how it may help enliven our imagination.

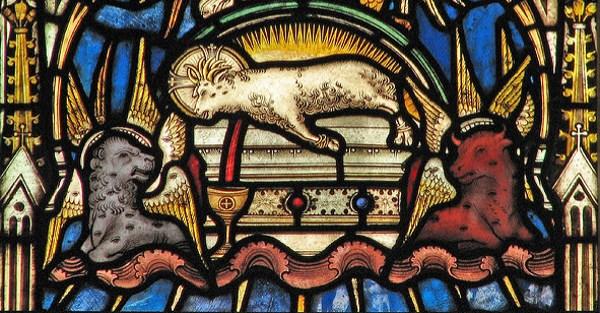

Barker enables us to recover the roots of what we now call the sacramental imagination in the imaginative visionary world of the priesthood of Solomon’s temple. Central to that vision are the ancient rites of Ascension or Enthronement, and the feast of the Atonement. It was the latter that was the principal feast of the year, not yet downplayed in relation to Passover as was the case by the time of Christ. The Holy of Holies in the Temple was conceived as standing in for ‘before’ the first day of creation: only God, Wisdom and the Holy Angels dwelt there. So the fullness of these rites, what they were fully about and meant, was conceived as already lived out in heaven. Hence their performance in the Holy Place. This fullness of rites and meaning is, then, strictly speaking, outside the order of time and narrative sequence. However, the fullness, on coming out from the Holy Place, interacts with time-structured sequential earthly reality in the form of the coming of Jesus, his teaching, his death and resurrection and the outworking of his prophesies concerning the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem in AD70. So the ‘fullness’ starts to become comprehensible as a series of human narratives, dependent on time and place. Each of the seven ‘seals’ opened by the slain-and-risen Lamb is a dimension of that narrative interaction between heavenly reality and earthly turbulence. And this gives us the form of the Book of Revelation.

How does this help us? Well, currently, we are inclined to imagine Atonement as principally to do with forgiving sin, and Creation as principally to do with causing everything to be. As a result of this, we relegate the Creation bit of our faith to the Father and the Atonement bit to the Son. We inherit from, and share with, the massively Creator-centred Jewish liturgy many phrases, like ‘Blessed are you, Lord God of all Creation’. Nevertheless, our discussion about the Eucharist tends to be focused on the ways in which we participate in what Jesus was doing in undergoing his death on the Cross on our behalf.

To put it briefly, this tends to feed into moralistic accounts of faith on both sides of the Reformation divide. These accounts see created order as something divinely pre-established, from which a human Fall provoked God into a reactive Redemption. Because of this, Creation becomes an historically distant and intellectually abstract backdrop to morality, and our Redemption very easily becomes some sort of moral struggle against our lower selves. Divine aid takes the form of Jesus having paid the price for our sins with his sacrifice, and then of our receiving living eucharistic tokens of that sacrifice to nourish us on our way through hac lacrimarum valle.

However, as Barker brings out in a number of places, the ancient rite of Atonement, long predating any of the lists of sins for which we assume it to have atoned, was far more weighted towards the unbinding, or renewing, of Creation than anything else. The idea behind it was that in a world created and orchestrated into being by God and God’s Wisdom, everything points towards, sings out, reflects, gives off, the glory of God; and those in whom Wisdom makes her dwelling are able to see this. However, over time, the cumulative effects of human transgression cause everything that is to become infected by vanity, or futility. Things no longer point to what is beyond them, and seem to wind down in entropy, dully going nowhere in particular, not quite hitting the mark; and humans too become blind and bound down in boredom and a sense of dissatisfaction. The rite of the Atonement was the moment when the Creator would come into creation (as High Priest) offering himself in sacrifice (as a lamb) so as to unblock all the blocked flows of things, disentangle all the entangled links of things, unbind all the bound-down things and people, cover over and protect the Creator’s chosen ones, and threaten requital against their enemies. Thus was the whole of Creation made glory-bearing, utterly alive, once again, and the sightedness of Wisdom restored to all.

It is this understanding, naturally, that underlies all those New Testament hymns and passages which have Jesus being the actual protagonist of Creation, having brought into the midst of Creation the chance, for which it had always been waiting, for it to become the fullness of what it had always been intended to be. What this means is that the fullness of the act of Creation and the act of Atonement, are the same act. While for us, in our usual temporal thinking, being must be prior to being forgiven, and so we imagine all sorts of ways of describing a ‘fall’ from some sort of ‘being’ that needs putting right. However, there is something much more exciting going on in the Christian faith than that: being and forgiveness are simultaneous, the new and the renewing are the same (so to make new and to repair in Hebrew have the same root): forgiveness and re-creation are the same.

So, imagine, if you will, a Creator, for whom there is no before nor after, neither past nor future. A Creator with an intense longing to share greater joy, to bring to life a project. Thus, in the midst of time (from the project’s point of view) or from before the dawn of time (our poetic way of talking about ‘outside any possible point of view’) an enactment is created such that humans can come to participate in the life of God. This magnificent festal reality is always already there ‘before’ temporality and is enacted slowly through time as we become able to detect, in our ghastly sacrificial rites, the hints, coming into our midst, of something that is undoing all that. Finally, the whole cosmetic act of Temples and slaughter of humans and animals is forever laid to rest when after centuries of preparation, the One who has always been ‘coming into the world’ does indeed come into the world, bereft of violent sacrality, and the real act of Creation is fulfilled in our midst.

What I would like to suggest is that this vision shifts Creation from being a more or less stable backdrop, one which needs protecting and restoring like a fragile Old Master, to being something that is, from our perspective, more like a new horizon that is reaching towards us to pull us in. Where we all start from is a not very stable, rather precarious backdrop, shot through with futility and a sense that any order we grab onto is part of a lie. Nevertheless, the whole daring project of Creation itself, has already been fulfilled in the midst of time. That fullness is already being lived out, such that from what seems to us like the future, that fullness, that Real Presence, is seeking to extend itself towards us constantly. It is bringing us into itself without any barrier now that death has been transformed from a power that dominates and impels our imagination, into the simple, gratefully accepted contour of that bodiliness thanks to which we can be formed into active participants in God’s life.

And this has an impact on how we live and celebrate the Eucharist. For the Eucharist is the most obvious way that the High Priest of Creation, the definitive Adam, breaks through into materiality so as to build us up into himself. He is not only feeding us ‘bread from heaven’ from a safe distance, as someone might give food to animals through bars until such a time as the animals become tamer company. The Creator and Redeemer is engaged in an act of daring. And I use that word in two senses.

In the first sense, ‘daring’ describes the project. It is crazily daring to desire, to imagine, and to bring into being this universe. It is even more daring to desire and to imagine ways in which a carbon-based life-form, a hypermimetic ape, one which had become even more dangerous to itself and to others than any of the other beasts, could possibly share in the life of God, be an active participant in bringing creative reality into being. An adventurous love is no less adventurous for being loving, even if the word ‘love’ has acquired for us so many connotations of domesticity. But how else do we describe the love that was not ashamed to enter into this life-form; to undergo the consequences of this life-form behaving in its most tediously predictable, shaming and murderous ways; and so to open up for this life-form a joy that is not bound down by any of those tendencies of ours?

In the second sense, what Jesus did was to dare us. In giving us his body and blood, and asking us to do it again, to summon through memory his sense of adventure into our present through the Eucharist, Jesus is daring us: ‘go on, take this and run with it’, which is to say, ‘go on, take me, I’m entrusting myself to you to make of me what you want.’ Or ‘I am happy to become who you will make me to be, daring you to make me something really amazing, more than can possibly be imagined right now’. That’s what he told his disciples before his Passion in John’s Gospel[2]. And this is why he breathed the Spirit into those gathered in the locked room on the evening of the First day, telling them that their capacity to forgive, to let go, was now going to be the defining factor in Creation. In as far as they dare to forgive, things will open up, and in as far as they don’t, they won’t[3]. Forgiveness and Creation having become entirely inseparable in the midst of time, we are dared to make of them something unimaginably more interesting, fun, and alive as we move through our lives.

What is meant by the doctrine of original sin is not that our race is forever stained by some ancient crime, but that we are the beings for whom Forgiveness is our access to Creation: it is in being let go, and letting go, that we are actually able to take part in discovering who we are and what we might be about. Forgiveness is not only an act of pity, which is where we tend to locate it, moralistically. It is far more than that: a creative act of mercy, implying equality of heart by One who is without any sense of superiority, but longs for our hearts to be stretched out into God’s own size.

So, when we allow ourselves to be brought liturgically into the Real Presence of the Festal Gathering that is already ‘just there’, longing to give itself away to us so that we may multiply joy, it might be worth remembering that Jesus’s daring in giving himself to us is part of the adventurousness of Creation. At the same time he is daring us to make of him something as yet unheard of and unseen. So, by faith we relax into being underpinned by his daring as our imaginations are opened out; by hope we dare allow ourselves to be stretched way beyond ourselves; and by love we come to discover that there is, and will, be no end to the splendour of the mess.

James Alison is a priest and theologian. The author of Jesus the Forgiving Victim – an introduction to the Christian faith for adults, among other works, he currently lives in Madrid, Spain.

[1] Margaret Barker The Revelation of Jesus Christ (Edinburgh:T&T Clark 2000)

[2] John 14:12: ‘Truly, truly, I say to you, he who believes in me will also do the works that I do; and greater works than these will he do, because I go to the Father.’

[3] John 20:22-23: ‘And when he had said this, he breathed on them, and said to them, ‘Receive the Holy Spirit. If you forgive the sins of any, they are forgiven; if you retain the sins of any, they are retained.’’