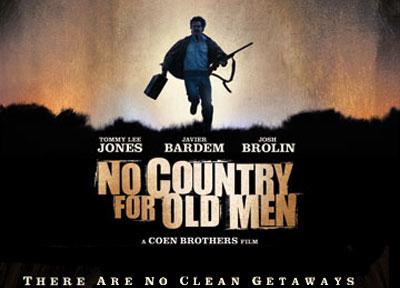

Starring: Josh Brolin, Javier Bardem, Tommy Lee Jones, Woody Harrelson

UK Release date: 18 January 2013

Certificate: 15 (122 mins)

If it weren't

for the guilt about carbon, there are certain points in the year when I yearn

to get a cheap flight to somewhere in the middle of middle America, hire a

suitably languorous vehicle, and drive aimlessly around the vast spaces,

stopping pointlessly at whatever isolated communities I find along the

way.

The Coen

Brothers' No Country for Old Men

intensifies this wanderlust - it is a film filled with loving images of

small-town America: elderly farmers in

Casey-Jones overalls drive pickups filled with chickens; preposterously grand

(but slightly seedy) three storey hotels sit in flat, half-empty one-horse

towns; polite, middle-aged ladies in fashions fifteen years out of date file

their nails in the management offices of trailer parks. But it is also a film filled with images of

casual and brutal violence: one of the

protagonists' preferred modes of killing is with the slaughterer's bolt-gun (a

subtle reference to Driller Killer,

perhaps): you might be filing your

nails one minute, you might be face-down on the desk, with your blood gently

oozing over the faux pine-finish floors the next.

The opening

sequences of the film indicate exactly how the next two hours will unfold. Firstly, there is the landscape: the camera ranges slowly and ravishingly

over the desiccated vastness of Texas - big, empty, dry. The sun at this point in the film slants

sideways across this emptiness, catching a hill here, a boulder there (is it

dawn or dusk you ask yourself). Secondly, there is evil, persistent, ruthless,

a-human. This element of the story

begins with an anecdote told by local sheriff Ed Tom Bell (Tommy Lee

Jones). A boy he sent to the electric chair

a few years previously had admitted to no remorse, had no fear of punishment,

and talked blithely of spending eternity in Hell. Worse, he had decided that the ability to kill - the desire to

kill - was part of who he was: if set

free, he'd just do it again.

One other man

set in this bleak beauty in whose nature it is to kill is Anton Chigurh (Javier

Bardem). Shortly after the prologue, we

watch the orgasmic pleasure on his face as he strangles a naïve local deputy

sheriff. And it is Chigurh's dark force

that drives through the film, relentlessly. There is something uncorruptible about this malevolence: he is the idea

of evil, he is 'a ghost', he 'has principles which transcend money or

drugs'.

So is raised one

of the central questions of the film: how can we respond to such evil? 'How,' asks Tommy Lee Jones' Sheriff Bell at one point 'do you defend

against it?' And the pessimism of the

film seems to lie in its contention that to take action against it risks

mirroring the evil itself, that in so doing, 'a man would have to put his soul

at hazard.'

It's almost as

though the film sets out to destroy four icons of American masculine purpose:

the sheriff, the cowboy, the outlaw and the Vietnam Vet. The sheriff is old and

despairing (even in his wisdom), the cowboy and the soldier become sucked up in

forces outside their control, and the outlaw is re-made into a dark angel -

elemental, dispassionate and disconnected. What intensifies the sense of doubt, perhaps even near despair, is that

the edges between these icons seem to have been deliberately blurred: the outlaw slaughters people as a rancher

kills steers, the cowboy hunts deer with a soldier's sniper rifle. All identities become confused in the

compelling vortex of evil, as tactics mirror each other, good purposes become

lost and only a casual malevolence has direction, stalking relentlessly towards

its own existential goal, following a series of blood-trails.

The script

explicitly raises theological questions: I am sure I heard Lee Jones ask his secretary 'What is it Torah says

about Truth and Justice?' I know she

replied that 'we dedicate ourselves daily anew'. It is centrally a story about mission, purpose and justice. We wait for judgement to come to Anton

Chigurh. But it doesn't. It is a fact

which mirrors one of Lee Jones' final lines in the film 'I always felt as I got

older that God would come into my life - he didn't'. All told, it seems fitting that the final frames of No Country for Old Men are a black

screen.

Ambrose Hogan

![]() Visit this film's official web site

Visit this film's official web site

![]()