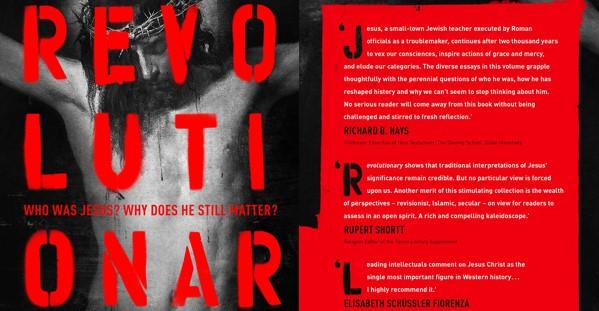

In his 2019 book, Dominion, Tom Holland advanced the case that in the course of its 2,000-year history, Christianity has had a distinctive and transformative effect on the social and ethical imaginations of the societies that it encounters. Particularly in the West, this shapes not just the expectations of individuals and the structures of institutions, but the nature of processes and movements for reform from within, providing the very language for criticising the failures and horrors committed by Christians (occasionally in the name of Christianity itself). Western atheism and communism are just as much products of the tradition as monasteries and orphanages. The revolutionary power comes ultimately from the teachings and life of Jesus of Nazareth himself, who again and again places the weak and the marginalised at the centre of ethical and theological attention, and becomes the living embodiment of their cause as the crucified victim of imperial power who is ultimately vindicated by God.

This engagingly written and thought-provoking collection of essays offers a set of responses, from a wide variety of viewpoints, which interrogate the core of that thesis. What is it exactly that Jesus brings that is so different? If he is a revolutionary, what sort of a revolutionary is he? It also tackles the natural further question of whether he can have the same transformative power in the modern era as in the past.

The range of starting points is helpfully broad. While most of the authors are comfortable reading traces of a real individual through the New Testament texts and against the background of Second Temple Judaism, the philosopher Julian Baggini bases his thesis on the absence of any access to a real, individual Jesus. Thus, while others try to identify the characteristics and distinctives of Jesus’s life and teaching, for Baggini their revolutionary power lies not in their definition in the New Testament, but rather in the ambiguities of Jesus’s narrative and his message. These Baggini explores, suggesting that they are what has given the Christian religious tradition its adaptive power through the centuries, with material to satisfy traditionalists and modernisers (on marriage, for instance), sometimes presenting as an insider group of the chosen and pure, destined for salvation, and sometimes as a group open to all-comers. ‘From the outset, Christianity was more adept than any other religion at making sure its product line appealed to a wider set of spiritual seekers than any other competitor.’ Jesus can be, so runs the argument, whatever you need him to be – and once you’ve identified him as such, you cease to notice any ambiguity at all.

Interestingly Amy-Jill Levine notes something similar, as she meditates on the meaning of ‘revolutionary’ for her students, who ‘require Jesus to be a revolutionary’ because they ‘need him for their own ideological agendas’. She wants this fascinating character to be a revolutionary, but in a way that is faithful to the texts. Her corrective is a careful testing of ‘revolutionary’ claims against real (rather than cardboard cut-out) Jewish text and tradition. There are two significant points of convergence with other contributors: firstly, Jesus is not a political revolutionary in the gun-toting, regime-changing sense; and secondly, when you look at the detail, it is actually hard to see anything in his teaching that separates it radically from its Jewish-Hellenistic roots. That said, while Robin Gill and Joan E. Taylor highlight the golden rule and enemy-love, or the priority of love, mercy and forgiveness as distinctives of Jesus’s teaching, Levine resists readings that would portray Jesus either as an ethical revolutionary against Jewish ‘particularism’ or as the radical defender of the poor and marginalised. On this, she argues, ‘the problem is that the texts do not support the claim’. She offers alternative readings of scenes such as the cleansing of the temple or Jesus touching a leper – Jesus is not being revolutionary, ‘he is just being kind’. His teaching sits well within the matrix of the writings of Leviticus, Deuteronomy, Proverbs and Jeremiah. ‘We do not need Jesus to tell us to feed the hungry, provide medical care, treat others with the same respect as we would like to be treated, or even see everyone – neighbour, stranger, enemy – as in the image of the divine. The message of care is already a part of Deuteronomy.’ Her conclusion is that Jesus’s revolutionary teaching lies in his storytelling, his parables. These are the things that ‘prompt us to see the world otherwise’ and question our presuppositions, and that challenge us to respond. This leads to a refreshing new look at some familiar texts, including the parables of the prodigal son and of the dishonest steward.

In different ways, Joan E. Taylor, Nick Spencer and Terry Eagleton present Jesus’s revolutionary ethic not just as a function of his teaching but of his teaching in the context of a life defined by the movement towards crucifixion. For Taylor – taking Mark’s Gospel as her lens and highlighting its dramatic structure – Jesus’s life’s work is a movement to overthrow the powers of domination and oppression that ultimately owe their power to the Johannine ‘ruler of this world’. So he is a political and social revolutionary, but on a cosmic, rather than a local scale. His death and resurrection vindicate a better, empowering way of forming community and by overthrowing the ‘ruler of this world’ present a genuine challenge to Roman, or indeed any other hegemonic claims.

Nick Spencer reads Jesus’s ethical teaching and his living enactment of it against the background of game theory. In a world where the pressure is on to go for a winner-takes-all, competitive version of human interaction, or one where we simply respond in kind to the way we are treated, Jesus presents a living model of what happens when we break a cycle of vendetta with forgiveness, or of deadly competition with restraint. ‘It is the moment when we don’t simply grasp at the limited resources in the fear that they will run out before we get any, but we wait with restraint and anxiety, in the hope that others will see our action and be similarly forbearing.’ We replace recrimination with restored relationship. This was Jesus’s revolution, ‘giving all he was in the awful daring of a moment’s surrender’.

Terry Eagleton takes as read that Jesus was executed as a political rebel but finds it highly unlikely that Jesus was indeed an anti-Roman insurgent. Jesus’s revolution is deeply rooted in the Hebrew vision of God’s saving activity, as revealed in the Magnificat. You will know God for who he is, ‘when you see the poor…coming to power’. God is a ‘terrorist of love, rather than a middle-class liberal’ and in that sense a revolutionist. Jesus comes to reveal the true face of God, not the satanic image of him ‘cultivated by those masochists among us who want a big nasty bastard of a God in order to be punished and thus be gratifyingly relieved of guilt’. Instead Jesus reveals God as ‘friend, comrade and lover, counsel for the defence rather than judge on the bench.’ That deep message of a constant call to the transformation of social relations coming from the heart of a loving God runs up against the concerns of the political establishment in Jerusalem to keep a lid on potential threats to order – threats made real by Jesus’s outraged challenge to them in the temple. It is this that leads to the expedient charge and his execution. ‘In the end, Jesus was killed because he spoke out fearlessly for love and justice in a political world that finds such things deeply threatening.’

Tarif Khalidi offers some fascinating insights into perspectives on Jesus within the Islamic tradition, his canonisation as a prophet of eschatological significance in the Qur’an and Hadith, and the emergence of a tradition of stories about Jesus, as a mystic and ascetic, withdrawn from worldly life, dubbed by no less than al-Ghazali as ‘a prophet of the heart’. As the Islamic and the Christian world re-encountered one another, controversy came more to the fore. But Khalidi highlights two Muslim texts from the 19th century that explore the political and religious significance of Jesus’s life and teaching as presented in the gospels. One includes a very un-Qur’anic meditation on the political significance of the crucifixion. Khalidi then presents an analysis of the way twentieth-century Muslim poets have used a revolutionary image of Christ – at once cosmic shaper of history and suffering human, victim and harbinger of a new world – as a figure to interpret the harsh political realities of Arabic history in the twentieth century. The lesson of this long ‘love affair’ between Islam and Jesus for Khalidi is that this record ‘has something to teach us about how religious cultures in general did, or perhaps even ought to, interact, enrich themselves and learn to coexist, to become complementary.’

A.N. Wilson focuses his discussion on the fourth gospel and its proclamation of a kingdom ‘not of this world’, entered through faith in Jesus. He notes that the milieu in which Jesus moves in the fourth gospel is predominantly well-to-do. He also finds a complete absence of a social gospel in this (or indeed any) gospel: ‘the pursuit of social virtue plays no part at all, as far as one can see, in the Gospel’ – by which he means there are no practical calls to poverty-relief or educational improvement. He attributes this to the fact that Jesus and his followers are ‘not merely non-social, but antisocial’. For them there is no future in the earthly city. The only future is for those who believe in the name of Jesus and inherit eternal life. Wilson sees John 6 (the feeding of the 5000) as pivotal. Jesus escapes from the crowd who want to make him king, rejecting any earthly regime change. The true nature of his revolution is only recognised by Peter at the end of the chapter, who stays with him when others go, and acknowledges, ‘you have the words of eternal life’.

Rowan Williams, like Eagleton, sees the execution of Jesus at one level as an impersonal act of brutal political expediency – Jesus is not dying for a cause, religious or nationalist, he is being removed as an inconvenient threat to public order. However, he goes on to draw out the multiple ways that Christian writers have sought to use motifs from the Old Testament to explain how Jesus’s death was an ‘intrinsic, even necessary, aspect of the way that divine agency is at work in the human story of Jesus so as to create the renewed community of God’s people.’ Whether they use the language of redemption or the language of ritual sacrifice and atonement, the multiple versions imply that a single fixed perspective will not do justice to the reality. Williams accepts with Baggini the unreachability of a person apart from the texts, and acknowledges the structural ambiguities embedded in the gospel texts of Jesus’s life and teaching, but sees this as creative disruption, summoning Jesus’s Jewish contemporaries to take the opportunity to rediscover their true identity, ‘an identity that is completely dependent on the free forgiveness and hospitality of God’. The moment of crucifixion, where the person ‘most fully in tune with the loving purpose of God’ is rejected as the archetypal enemy of that purpose, brings the disruptive nature of Jesus’s preaching into dramatic focus.

This suggests two ways in which this story can continue to exercise a transformative power. In one step, we are invited to imagine a human community before a God of grace and mercy, that does not depend for its formation on human power and interests and that does not apportion status according to background or performance. In a second and decisive step we are invited to imagine that those ‘who have experienced loss, powerlessness and victimization are the proper focus and test for any scheme of human meaning’. No viable philosophy of human society can regard ‘humiliation and exclusion as ignorable or inevitable or justifiable.’ For those with faith in God, that God is to be found in complete solidarity with those who suffer. For those who struggle with that bit of the transcendent, the cross of Jesus nevertheless confronts us with the enduring challenge that suffering has an unqualified claim on our attention and response.

The reviewer, John Moffatt SJ, is studying for a PhD in Medieval Islamic Philosophy at the School of Oriental and African Studies.