1 May is the Feast of St Joseph the Worker, a day on which the Church encourages us to celebrate the value of work, and the dignity and rights of workers. These issues are already in sharp focus this week for Londoners, due to strike action by London Underground workers. John Battle asks to what extent the understanding of trade unions in Catholic Social Teaching matches that of the late union leader, Bob Crow.

Any London-based readers are likely to be heading into the Feast of St Joseph the Worker on 1 May having experienced the chaos of a two-day tube strike organised by the Rail, Maritime and Transport Union (RMT), the second such strike to take place this year. The public attitude to this industrial action, which caused widespread disruption to London’s transport network, has been largely unsympathetic. The fact that industrial strikes are an increasingly rare occurrence (not least because it is now legally much harder for union members to take such action) has meant that, when they do occur, they are regarded by many as throwbacks to a bygone age that have no place in a modern economy. Yet the struggle for justice at work – including the right to organise and withdraw labour – is considered carefully by the Church in its tradition of promoting social justice.

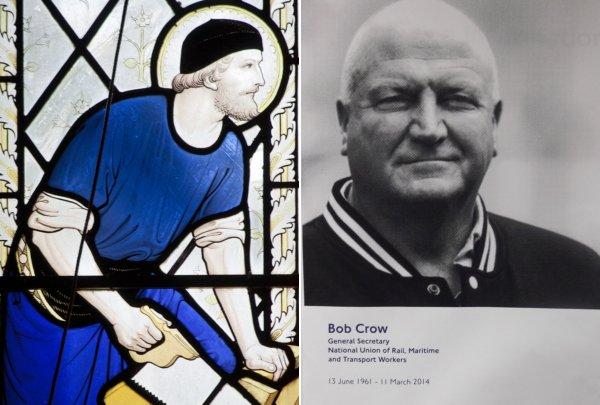

How do the aims of the RMT, and particularly those of the late Bob Crow, the man who championed its cause, measure up to Church’s support for and challenge to trade unions?

Trade unions in Catholic Social Teaching

On 1 May 2000, on the occasion of the Jubilee Gathering of Workers in Rome, Pope John Paul II issued an appeal for ‘a global coalition in favour of “decent work”’, in support of a campaign by the International Labour Organisation.[i] More recently, in his encyclical Caritas in veritate, his successor Pope Benedict XVI defined ‘decent work’ as:

...work that expresses the essential dignity of every man and woman in the context of their particular society: work that is freely chosen, effectively associating workers, both men and women, with the development of their community; work that enables the worker to be respected and free from any form of discrimination; work that makes it possible for families to meet their needs and provide schooling for their children, without the children themselves being forced into labour; work that permits the workers to organise themselves freely, and to make their voices heard; work that leaves enough room for rediscovering one’s roots at a personal, familial and spiritual level; work that guarantees those who have retired a decent standard of living.[ii]

But how is this expansive vision of work to be realised? A decrease in emphasis on unions as the principal method of expressing solidarity in the world of work has led to an increasingly common view that trade unions are becoming irrelevant in our economic and social context. Today trade unions tend to be regarded as dinosaurs, locked into an earlier economic and industrial structure of mass manufacturing and production that has been swept aside by globalisation, outsourcing and rapid transportation. Yet labour unions remain the primary means of ensuring association among workers and of facilitating negotiations with employers in order to secure the advancement of worker conditions and the promotion of the dignity of human labour. John Paul II went as far as to suggest that trade unions are ‘a mouthpiece for the struggle for social justice’[iii], and both the encyclical from which that description comes, Laborem exercens, and the later Centesimus annus follow a tradition that stretches back to Leo XIII’s Rerum novarum (1891), which first underlined the role of trade unions.

Bob Crow

The afore-mentioned present dispute is over staffing plans for London’s tube stations. The RMT’s cause was led until March 2014 by its recently deceased leader, Bob Crow, a divisive leader who was vilified in life but, to the surprise of many, deified in death. Born into a trade union family in East London in 1961 (his father, a docker, was a member of the Transport and General Workers Union), Crow left school at the age of 16 and went to work for London Transport. In 1983 he became a local trade union representative for the National Union of Railwaymen and progressed through its ranks. That union, after a merger in 1990, became the RMT, of which Crow became General Secretary in 2002.

Bob Crow worked tirelessly to popularise the cause of trade unions at a time of declining membership, legal opposition and increasing public hostility. Under his leadership, membership of the RMT rose from 59,000 to 78,000 and wages in the industry increased faster than the average. Ken Livingstone, who, when he was Mayor of London, had to negotiate with Crow, once commented that, ‘the only working class people who still have well paid jobs in London are RMT members’. Under Crow’s leadership the friction between the RMT and the other rail unions, ASLEF and the Transport Salaried Staffs’ Association, was eased into cooperation. Crow capitalised on the fact that he was (in contrast to other trade unions) in a booming sector: doubling passenger numbers meant that his union still had real power – the power to withdraw labour and thereby effectively paralyse the transport network, especially the London Underground, as has been seen this week.

Representing the unrepresented

Bob Crow was clear and passionate about his role as a union leader: ‘If you join [a trade union] you expect it to fight for your rights and your job – and that’s what I’m doing.’[iv] But he also had a reputation for defending the rights of low-paid workers, including outsourced cleaners, even in the face of criticism from his own executive committee. This wider remit of trade unions was supported by Benedict XVI in Caritas in veritate:

The global context in which work takes place also demands that national labour unions, which tend to limit themselves to defending the interests of their registered members, should turn their attention to those outside their membership, and in particular to workers in developing countries where social rights are often violated.[v]

That encyclical also highlighted the dangers of robbing workers of their dignity:

In many cases, poverty results from a violation of the dignity of human work, either because work opportunities are limited (through unemployment or underemployment), or ‘because a low value is put on work and the rights that flow from it, especially the right to a just wage and to the personal security of the worker and his or her family’.[vi]

Crow’s own commitment to his members echoes this concern: ‘RMT have made it clear we expect managers to abide by the existing job security arrangements and we would simply not be doing our job as a union if we allowed the tube to treat our members as cannon fodder who can be hired at will.’[vii]

It could also be argued that the RMT leader followed more of Pope Benedict’s guidance:

The Church’s traditional teaching makes a valid distinction between the respective roles and functions of trade unions and politics. This distinction allows unions to identify civil society as the proper setting for their necessary activity of defending and promoting labour, especially on behalf of the exploited and unrepresented workers, whose woeful condition is often ignored by the distracted eye of society.[viii]

Crow was certainly no friend of the major political parties. He condemned former (Conservative) Prime Minister John Major’s privatisation of the railways and later accused Tony Blair’s (Labour) government of, ‘pouring billions of public pounds into private pockets and [accelerating] the growing gap between rich and poor’.[ix] The RMT was then expelled from the Labour Party in 2004 for coming out in support of another party. Bob Crow himself died a member of no political party. He was keen to spread his brand of activism across the entire trade union movement, consistently backing groups of workers in their local struggles in the hope of ‘heightening militancy and creating fresh opportunities for action’. Challenged over his opposition to the European Union, he clarified that he was, ‘not against workers coming into this country [but against] two workers from different countries competing against each other on different rates of pay’.[x]

Workers versus consumers

Not only have labour unions ‘always been encouraged and supported by the Church’, says Pope Benedict, but he insists that ‘they should always be open to the new perspectives emerging in the world of work. Looking to wider concerns than the specific category of labour for which they were formed, union organisations are called to address some of the new questions arising in our society’, such as the new conflicts ‘between worker and consumer’.[xi] Crow’s critics might argue that he sacrificed this wider perspective in favour of a single-minded pursuit of the particular aims of his own union. He was accused repeatedly just before his death of holding London to ransom with strikes and placing his union members above other working people.

Crow’s supporters, however, would say this was no bad thing. On his death, The Telegraph commented that, ‘Crow wanted the best deal for the people who paid his salary, and they continued to reward him because he delivered it’.[xii] In his own words: ‘I don’t shirk from taking industrial action. Our job is to negotiate the best pay and conditions. Industrial action is the last resort and you don’t take it lightly - but when you start you don’t finish until you have won. That’s what I have been brought up on.’[xiii]

Work as the Key Social Question

Crow had a reputation for keeping his word once he had struck a bargain, and those who negotiated with him did not take the view that he rushed to disrupt. One manager who negotiated with him commented, ‘Yes, he wanted to change the world, but he saw his first task as bettering the lot of his members rather than encouraging some kind of revolution’.[xiv] Crow was renowned for his ‘militancy’ but always saw his primary role as improving the lot of his members. His union’s motto was ‘Agitate, Educate, Organise’. He became the face and voice of trade unions in the media, and said that he strived for: ‘Job security, being safe, best possible pay, best possible working conditions, decent retirement conditions, and a world that lives in peace’.[xv]

A concluding reflection, in light of which we can evaluate Crow’s commitment to his cause and the role of trade unions in general, should rest with our new Saint John Paul II. These words are from his introduction to the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace’s symposium, Work as the Key Social Question:

The rapid and accelerated period of change in the world calls for the overcoming of the current view of the economic and social system in which human needs, especially, are accorded only a limited and inadequate consideration. In contrast with every other living being, man has infinite needs, because his being and his vocation are defined by reference to the transcendent. Starting from these needs, he tackles the adventure of transforming reality with his work according to a dynamic impulse that always goes beyond the results achieved by it.

... new forms of solidarity must be created, taking into account the interdependence that forges bonds among workers. If the changes in progress are profound, there must be a correspondingly intelligent effort and the will to protect the dignity of work, strengthening, at various levels, the interested institutions.

…All are called not only to foster these interests in an honest form and through dialogue, but also to rethink their own functions, their structure, their nature and their kinds of action…these organisations can and must become places where workers can express his/her own personality. [xvi]

Perhaps, on the Feast of St Joseph the Worker, we should all make sure we are paid-up members.

John Battle is involved with credit unions in his local community and in building ‘Leeds Citizens’ community organising network.

[i] Pope John Paul II, Greeting after Mass, Jubilee of Workers (1 May 2000): http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/john_paul_ii/speeches/2000/apr-jun/documents/hf_jp-ii_spe_20000501_jub-workers_en.html

[ii] Pope Benedict XVI, Caritas in veritate (2009), §63: http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/benedict_xvi/encyclicals/documents/hf_ben-xvi_enc_20090629_caritas-in-veritate_en.html

[iii] Pope John Paul II, Laborem exercens (1981), §20 (emphasis original): http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/john_paul_ii/encyclicals/documents/hf_jp-ii_enc_14091981_laborem-exercens_en.html

[iv] ‘Bob Crow: Bolshy, argumentative and unapologetic but a man you would want to fight your corner’, The Mirror (9 Feb 2014): http://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/bob-crow-bolshy-argumentative-unapologetic-3127064#ixzz2wbwQlLnG

[v] Pope Benedict XVI, Caritas in veritate, §64

[vi] Pope Benedict XVI, Caritas in veritate , §63 (emphasis original)

[vii] Bob Crow, ‘Tube workers won’t be bullied’, The Guardian (9 June 2009): http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2009/jun/09/london-underground-tube-strike?commentpage=6

[viii] Pope Benedict XVI, Caritas in veritate, §64

[ix] ‘Bob Crow – obituary’, The Telegraph (11 March 2014): http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/10689458/Bob-Crow-obituary.html

[x] ‘Crow launches NO2EU euro campaign’, BBC News (22 May 2009): http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk_politics/8059281.stm

[xi] Pope Benedict XVI, Caritas in veritate, §64

[xii] ‘Bob Crow: a n unlikely capitalist’, The Telegraph (11 March 2014): http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/newsbysector/transport/10690180/Bob-Crow-an-unlikely-capitalist.html

[xiii] ‘Bob Crow obituary: A working class hero who never shirked from industrial action’, The Independent (11 March 2014): http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/bob-crow-obituary-a-working-class-hero-who-never-shirked-from-industrial-action-9183811.html

[xiv] ‘Bob Crow obituary’, The Guardian (11 March 2014): http://www.theguardian.com/politics/2014/mar/11/bob-crow

[xv] ‘Bob Crow: The union leader everyone had heard of’, BBC News Magazine (11 March 2014): http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-26529781

[xvi] Pope John Paul II, Message to the International Symposium run by the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace on the theme ‘Work as the Key to the Social Question’ (14 September 2001), §3-4 (emphasis original): http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/john_paul_ii/speeches/2001/september/documents/hf_jp-ii_spe_20010914_incontro-lavoro_en.html