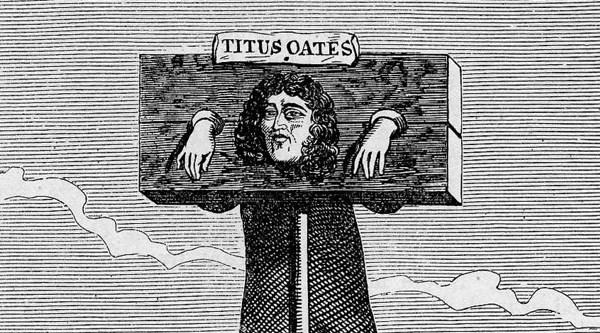

This weekend is the anniversary of the death in 1705 of the chief inventor of a conspiracy theory which accused Catholics, and Jesuits in particular, of planning the assassination of King Charles II. Daniel Kearney introduces Titus Oates, a man of mischief whose Popish Plot led to great misery for English Catholics.

Andrew Marvell caught the mood of the nation when he claimed in 1675 that ‘Popery is such a thing as cannot, but for want of a word to express it, be called a religion.’[i] Catholicism in England had gained this reputation through its association in the preceding one hundred years with various plots to depose or assassinate Queen Elizabeth I (for example, the plots associated with the names Ridolfi, Throckmorton and Babington), and of course with the Gunpowder plot. If Catholics in general were bad, then the Jesuits were worse. The distinction in statutes and proclamations of the time between ‘priests and Jesuits’ testifies to this reputation.

It was against this backdrop of fear of Catholic conspiracy that, in the autumn of 1678, Titus Oates and his followers sought to implicate the Jesuits as the architects of a plot to assassinate Charles II and overthrow the Protestant establishment. As a result of their claims, hundreds of Catholics were imprisoned and 24 executed; among them were John Plessington, John Lloyd and Philip Evans, three of the forty martyrs of England and Wales canonised by Pope Paul VI in 1970.

Oates had been received into the Catholic Church in March 1677, but he would later claim that his conversion was insincere and merely part of his ploy to infiltrate the Society of Jesus. Remarkably, he managed to gain an introduction to Richard Strange, the English Provincial of the Jesuits who arranged for Oates to go to the English College at Valladolid. Strange has attracted a great deal of criticism for his willingness to accept Oates, who was already something of a disreputable character. However, some have argued that to understand how Oates came to be received at the College one must take into account Catholicism in England at the time: the Catholic community was declining; and the clergy showed a lack of discipline and low morale, not helped by the absence of an ecclesiastical superior since the exile to France of Richard Smith in 1631. Many clergy gravitated to London not concerned with the evangelisation of the masses but attracted by the hope of securing a chaplaincy with the gentry. Among such a dissolute group, Titus Oates would have passed unnoticed.

Oates arrived at Valladolid on 1 June 1677 but a few months later he was expelled ob pessimos mores. The Jesuit rector, Father Manuel de Calatayud, admitted that he accepted Oates ‘very much against the grain’ and ‘kept him in lay dress all the time’, but ‘he was in such a hurry to begin his mischief that I was obliged to expel him from the College. He was a curse.’ [ii]

Even after his expulsion from Valladolid, Oates kept in touch with the Society and was received at the Jesuit college at St Omer under the alias Stampson Lucy. He was sent from there to the nearby seminary at Watten for an interview to assess his suitability for entering the Jesuit novitiate. The rector immediately formed a very poor opinion of him and suspected that he was not what he appeared to be, ‘but sent as a spy’ (an intention to which Oates would later admit). On his return to St Omer, Oates was subsequently expelled. Back in London and penniless, he renewed his friendship with Israel Tonge.

Tonge was a crazed clergyman who believed that the Society of Jesus was responsible for the Great Fire of London in 1666 and for the execution of Charles I. Tonge had also always believed in the existence of a ‘Popish Plot’ to assassinate Charles II, but before he met Oates he was unable to persuade anyone of influence that such a plot existed. Oates was able to provide him with detailed, first-hand knowledge of the English Province of the Society of Jesus and its European activities. Tonge encouraged Oates to put down on paper all he had heard and seen on his travels; Oates, fired up with hatred of the Jesuits, constructed a detailed and vivid story, set out in 43 numbered paragraphs, of a conspiracy to assassinate the King and to raise a rebellion in all three kingdoms. The rebellion would commence in Scotland and the Jesuits, disguised as Dissenting ministers would, of course, be the catalyst.

Through an intermediary, Christopher Kirkley, who was associated with the royal laboratory, Tonge made contact with the King. He informed Charles of the more important details of the story including, in particular, Oates’s claim to have heard during his time at Valladolid that the English Jesuits, led by George Conyers and John Keynes, were planning to assassinate the King. Oates maintained that the Spanish Jesuits had offered £10,000 in aid of the good cause.

Oates’s narrative was a wild and sordid mixture of his own furtive imagination, gossip and malice. He took the opportunity to implicate Catholics whom he had perhaps had a disagreement with or held a grudge against, for example the Benedictine Thomas Pickering, who was rewarded with a leading role in the plot for turning Oates away when he had arrived in London penniless after his expulsion from St Omer and was begging for his supper. As the plot thickened Oates seems to have brought into it any Catholic whose name he knew. He even attempted to implicate Charles’s ambassador in Madrid, Sir William Godolphin who was rumoured to have become a convert to Catholicism.

According to Oates’s narrative, Pickering and a Jesuit lay brother, John Grove, had vowed to shoot Charles; and if that was unsuccessful, Sir George Wakeman, the Queen’s physician, was to poison him. Oates claimed that Pickering attempted to shoot the King in St James’s Park but his pistol failed to fire. He also claimed that the Jesuits had been offered the use of four Irish ruffians to dispatch the King.

Some commentators have argued that it would be naïve to dismiss Oates’s claims as nonsense, that there was some truth to be found in the accusations, however vague they may have appeared. Whatever the status of Oates’s story, its effects were very real: it was taken sufficiently seriously to warrant a thorough investigation by the Earl of Danby, Charles’s Lord Treasurer and Chief Minister, and this brought misery and suffering to many.

When news of the plot broke out, a wave of paranoia spread throughout the nation. A state of emergency was declared in London, and there were constant reports of invading forces landings at numerous ports. The Jesuits bore the brunt of this hysteria: nine were executed, including the Provincial, Thomas Whitbread (who had been responsible for Oates’s expulsion from St Omer); twelve died in prison; and three others met their death as a result of the plot. Oates became the most popular man in the country and styled himself as the ‘saviour of the nation’. He took on the title of Doctor, which he claimed had been bestowed on him at the University of Salamanca… but there is no record of him ever having visited Salamanca, despite his return journey from the English College at Valladolid being well documented.

After the furore of the plot had quietened, Oates received several royal pensions, but on 10 May 1684 he was arrested at the Amsterdam coffee house on a writ of scandalum magnatum for referring to the Duke of York as ‘that traitor James’. The King’s Bench found him guilty as charged and he was ordered to pay the huge sum of £100,000 in damages. Oates was, of course, unable to pay and was thrown into the debtor’s side of King’s Bench prison. This was not the end of his woes. He was subsequently charged with two counts of perjury in relation to his evidence given against some of the alleged conspirators of the Popish Plot and he was arraigned on 6 February 1685. After a lengthy trial he was found guilty of the charge.

As he handed down Oates’s sentence, Sir Francis Wythens remarked, ‘I do not know how I can say but that the law is defective that such a one is not to be hanged.’[iii] Instead, Oates was defrocked, fined 1,000 marks on each count of perjury and imprisoned for life, which was to include him standing in the pillory on five specified dates every year. This was in addition to the whippings on the days that immediately followed his conviction.

Despite having been given a life sentence, Oates was released from prison in December 1688 and on 11 March 1689 he audaciously petitioned Parliament for redress. After several postponements, proceedings finally commenced on 17 May. The judges who had presided over his original trial for perjury (with the exception of George Jeffreys, who was confined in the Tower) were forced to justify their actions. They argued that Oates’s case was unprecedented and they had sought to make the punishment fit the crime. Oates failed to have his sentence and punishment overturned and was remanded to the King’s Bench prison yet again.

Finally, after lengthy legal wrangling about the legitimacy of Oates’s punishment he was given a free pardon by King William of Orange, who also granted him an allowance of £10 a week. Oates settled down in Westminster to write anti-Jesuit tracts and married a wealthy widow, which increased his personal fortunes. He died in Axe Yard on 12 July 1705.

No evidence has ever come to light to substantiate Oates’s plot and no historian of any standing has professed to believe in it.

Daniel Kearney is a former headmaster at an independent Catholic college. He is currently Head of Religious Studies at Leweston School in Dorset.

[i] Marvell, Andrew, An account of the growth of popery, and arbitrary government in England (1675)

[ii] Calatayud, Manuel, in Williams, Michael E., St Alban’s College Valladolid – Four Centuries of English Catholic Presence in Spain (1986)

[iii] Kenyon, John, The Popish Plot (1972)