How does it feel to take a bird’s-eye view of your own life? Paddy Gilger SJ has found it a little disconcerting as his parents have told us how they engaged with his vocation to the priesthood; he has been a character in somebody else’s story. But in the strangeness of the experience, there has been something sacramental: he has found honesty, beauty and love.

Can we agree up front that it’s weird to be a character in someone else’s story? I mean, that it’s strange, that it’s a little disconcerting, to read about the ripples one makes in others’ lives?

It’s a little like sitting in the pew during your own eulogy. Or, that’s kind of what it’s been like for me as I’ve read about the feedback that, like a Jimi Hendrix song, whined through my parents’ lives because of me and my decision to become a priest.

One of the main sources of this strangeness is that it’s someone else who is picking which tales to tell. Some of the stories they told… I wouldn’t know how to react to them at any age. I mean, what am I supposed to say about having been baptised on a day when the clouds were so thick that the sun seems to have broken through only once? That the rays fell just so and just as the priest poured the water? I didn’t choose that. I didn’t make it happen. What am I supposed to say about a story like that?

Sure, it’s beautiful and (although my mother is not above exaggerating my virtues) true. But that does not make the story – for me – unproblematic. The problem is this: a story like that makes my life seem like destiny. It makes it seem as if my life has been a one-way street and all I did was drive along it. And maybe in a way that’s true. But it never felt like that while I was living it.

If I had told the same stories, I would have told them in a different way. They would have been first person stories, stories about what it’s like to only be able to see 140 degrees. Sure, sometimes things are clearer in the moment that way, but rarely as clear as from the bird’s eye.

Or maybe I would have told different stories altogether. I would have told the stories where I’m blind, the ones where it felt like I was tracing a line of brail down a page only to find a sudden emptiness, a gap caused by some typesetter’s error or practical joke. And afterwards the line breaks in a dozen directions, like roads off a roundabout, each of them readable, each able to make sense of the markings that came before.

I would have told stories about feeling – steadily, gently – beckoned by the light that is joy. I would have told stories about what it’s like to have to fight to follow it.

But I don’t want to oversell the point. Because there are (at least) two things to be said about the stories my mom and dad told that are more important than the fact that it’s been weird to be a character in their stories.

The first is that what they wrote – what my mom and dad wrote about themselves and me and God and the Church – it’s honest.

It’s honest for the normal reason: because they pulled back the layers that humans place between our wounds and the world to let us see in. And what we saw was beautiful. Honesty made what they wrote beautiful.

The second more important thing is that their essays weren’t really about me (they weren’t really about them either, but they sure weren’t about me); their stories are really about us. They’re stories about what ‘us’ means and who gets included in us and how us gets made and what has to be sacrificed to make us.

Their stories are evidence that I cannot include in my life anyone or anything that my parents will not try their damnedest to include in theirs; that whoever becomes a part of my ‘us’ is in theirs, too.

Which is why their words are only partially the story of how a good man and a good woman responded to the pressures, the friction I put on them. It’s why they’re only partially about how the freedom they gave me demanded alterations in their own. It’s why their stories are only partially about the tensions that my choices created for us. It’s why they’re really about them choosing to create us anyway.

All that is why when I read what they’ve written it’s gratitude I feel, a lot more than strangeness. Or better, it’s amazement that what they want more than autonomy is relationship. Or even better still, it’s that in the best way, in the least degrading way, I feel unworthy to be the recipient of their love, to have been made by it.

I think that’s really what my parents’ essays are: they are a making tangible (well, digital) of love. Their essays are sacraments.

My own life more or less comes down to a response to having been well loved by them, by others, by God.

My life comes down to my having been one of the well loved in this world.

***

(Now comes the – stick with me – semi-mandatory coda on religion.)

Real religion is handed down over the years like your grandfather’s smoking jacket, like an old family joke with all the edges worn smooth.

Real religion is a sacrifice made to preserve the experience of ‘having been loved’ when it’s so much easier to just let it go.

Real religion is an actual re-ligio, a binding together again of those who would otherwise fly apart.

In other words, real religion? It’s an us.

And it’s what I want my whole life to be about. It’s why I am a priest today, why I want more than anything (more than having a family, more than having a polished persona) to be a conduit of that immense and merciful love that precedes us and follows us on our way. I hope you have felt well loved like that, too.

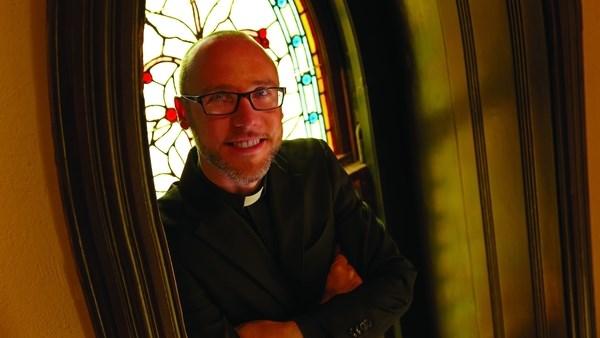

Paddy Gilger SJ is a pastor, writer, spiritual director and teacher of sociology at Creighton University. He is the founding editor-in-chief of The Jesuit Post — a social media project that makes the case for the relevance of faith in our secular age — and the editor of The Jesuit Post, which was published by Orbis Press in 2014.

- Paddy's mother, Kristin, reflects on his vocation to the priesthood: 'She was much perplexed by his words'

- Gary Gilger, Paddy's father, writes about his son the priest: 'When his parents saw him they were astonished'