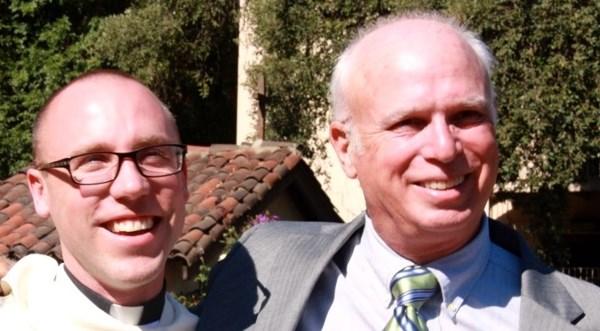

19 March is the Feast of St Joseph, a day on which we celebrate fatherhood. In this, the Year of Consecrated Life, we asked Gary Gilger to tell us how he reacted to his son’s vocation to become a Jesuit. After questions, doubts and adjustments, how does he feel now when he talks about, ‘my son the priest’?

In the winter of 2001, my son, Patrick, then a senior in college, announced he would be bringing someone home to ‘meet the parents.’

It wasn’t a young woman, as we might have expected. It was a priest: Father Warren Sazama SJ, the vocations director for the Society of Jesus, better known as the Jesuits.

‘You’ll get to meet him and he’ll get to meet you,’ Patrick said. ‘It’ll be great.’

We were polite when Father Saz, as Patrick called him, arrived at our house a few months later. We sat down to dinner with my wife, our two teenage daughters and my 80-something mother and chatted about the girls’ high school, our life in Phoenix and the weather – everything except what he had come to talk about.

It wasn’t until after the plates were cleared and coffee was served that Father Saz popped the question. ‘I don’t know how much Patrick has told you about his interest in becoming a priest, and I’m sure this raises a lot of questions for you,’ he said. ‘But we think he may have a genuine vocation. Is this something that surprises you?’

My wife, Kris, and I looked at each other for a long second before responding simultaneously. ‘Yes,’ I said. ‘No,’ she said.

Her ‘No’ surprised me. We hadn’t talked much about Patrick’s sudden interest in becoming a Jesuit priest, but why wouldn’t she be surprised by it? We had been married in the Catholic Church and our children had been baptised Catholic, but it had been years since we called ourselves Catholic. Who would ever have guessed he would consider a vocation like this?

As if she could read the questions forming in my mind, she began to tell the story of Patrick’s baptism. How it was a bitterly cold, cloudy day without a hint of sunshine. How, just as the priest began to pour the water over our son’s head, the sun broke through the stained glass and lit up the baby at the font. How we all laughed nervously and the priest said, ‘God must have something special in mind for this baby.’

She went on to talk about other moments in his life when she was reminded that he was spiritual in a way that neither of us fully understood.

I wasn’t so sure. Patrick was always a good kid. I can’t remember ever punishing him for being disobedient, except maybe when he teased his sisters a little too much. Maybe my wife was right and he had a deep spiritual side; but all I could think about was the little boy who loved Star Wars and Lego, and collected baseball cards, and who dreamed of growing up to be a doctor like my brother.

It was because he wanted to become a doctor that we sent him to Creighton University, a Jesuit college in Omaha, Nebraska. But after a couple of years of taking science classes, he called one afternoon and told us that while he could get through biochemistry, he would rather study philosophy.

Our first reaction was: what in the world was he going to do with a degree in philosophy? Think deep thoughts? Patrick’s answer was telling: there is nothing more important than figuring out the meaning of life, he said, nothing more critical than learning how to live well.

For a long time my wife and I thought that Patrick’s interest in philosophy and religion were passing fads. He was an idealist young college kid, and idealist young college kids try all kinds of things and entertain all kinds of notions that don’t last.

I had never thought of us as a particularly religious family, although we took the children to church (an Episcopal church) each Sunday, taught them their prayers and said grace before meals. We wanted them to be moral, ethical human beings. We wanted them to grow into the kind of people who care about and care for others.

But a priest? I could imagine Patrick as many things – a doctor, of course, but also a scientist, a musician or teacher. And most especially a dad. I had always thought he would make a great dad. Priests, on the other hand, are people who live solitary lives without the love of family. They’re the people who pass judgment on others, who enforce rules and talk to God.

It took me a long time to get used to the idea of my son as a priest, and even longer to adjust my view of what it means to be a priest. (It helps that Patrick is one of the least judgmental and most loving people I know.) I still don’t understand what it means to have a personal relationship with God, but I trust that my son is doing what’s right for him – and very possibly what God wants him to do.

Eleven years after Father Saz’s visit and with Patrick’s ordination behind us, I’m a lot more comfortable saying, ‘my son the priest.’ It seems almost normal.

Has it changed me, though? I guess the answer is both ‘yes’ and ‘no.’ I attend Mass more often and probably get into more frequent discussions that border on religious, but those things are unavoidable when your son is a priest. Patrick enjoys the verbal joust, and he’s very good at it. I cannot compete with him when it comes to justifying positions. He knows his stuff a lot better than I do so most of the time I just try to stay out of the way.

I know that his beliefs – and everything he does – are based on a deep faith that I will probably never have. I think of myself as a good person who did his best to raise his family well, who works hard and treats others well. This is enough for me. I have no desire to convince others to think as I do.

I think Patrick understands this and tries not to push me too hard, figuring that I’ll either come along or I won’t. But either way, he knows that I love him and have the greatest respect for all he does.

This past Christmas, my wife and I flew to Nebraska to spend the holidays with Patrick. We went to plenty of Masses and met many of Patrick’s Jesuit colleagues and the people who attend the church on the Creighton campus where he is interim pastor. We were overwhelmed by how much he is appreciated and loved. People told us over and over what a difference he has made in their lives and what a wonderful job we did raising him – the kind of praise any parent would love to hear.

I can see that his faith in God is very good for him, and it’s very good for those whose lives he touches every day. He makes a difference; that’s what he wants to do and his faith helps him do it. That’s something. That counts.

Not everybody gets to make a difference in the world. Not everyone gets to follow their passion and lead with their heart and mind and soul. Patrick is lucky. The Jesuits are lucky to have him as part of their order of men of faith. And I’m lucky to have him as a son, too.

Gary Gilger is a graduate of the University of Nebraska-Omaha. He worked in student affairs before staying at home to help raise children for 15 years. He now works for Pearson Education in Mesa, Arizona and has been active in Democratic politics in Phoenix, AZ for the past 6 years.

Patrick’s mother, Kristin, tells her side of the story.

Title taken from Luke 2:48.