This year, the UN refugee agency (UNHCR) marks the 60th anniversary of the 1951 Refugee Convention. Concluding Thinking Faith’s series for Refugee Week 2011, Amaya Valcarcel, Jesuit Refugee Service International Advocacy Coordinator, considers the aptness of the law to deal with forced displacement today.

The 1951 UN Convention relating to the status of refugees is rightly considered to be the cornerstone of refugee protection. However, 60 years after it was enacted, many question whether this law is now outdated. Certainly its definition of who is a refugee does not cover all modern displacement situations.

The legal category of 'refugee' set out in the Convention was created at a very particular time in history and intended mainly to address the plight of Holocaust victims, other refugees from the Second World War and new refugees from central and eastern Europe. Even if improved by the 1967 Protocol, the definition remains relatively narrow, covering only people fleeing individual persecution by their governments.

Although limited in scope, the Convention arose out of a much broader recognition that where states are unable to offer de facto or de jure protection to their citizens, the international community has an obligation to offer protection. In practice, however, the Convention definition has never captured the totality of circumstances under which people are forced to leave their home and country due to an existential threat.

Taking a broader view

JRS knows from first-hand experience that many people fleeing desperate situations cannot access the protection offered by the Convention. In a letter to JRS to mark its 30th anniversary, the Jesuit Superior General, Fr Adolfo Nicolás SJ, talks of ‘many new forms of displacement, many new experiences of vulnerability and suffering’. The UN refugee agency, UNHCR itself recognises that there is a range of 'people on the move' who fall outside the remit of the Convention but who nevertheless have protection needs.

Other refugee definitions are wider in scope, namely the Convention of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) and the Cartagena Declaration, the provisions of which are respected across Central America. The Church also takes the broader view. A 1992 Vatican document entitled ‘Refugees: A Challenge to Solidarity’ offers a new refugee definition, that adopted by JRS:

In the categories of the International Convention are not included the victims of armed conflicts, erroneous economic policy or natural disasters. For humanitarian reasons, there is today a growing tendency to recognise such people as de facto refugees, given the involuntary nature of their migration…

A great number of people are forcibly uprooted from their homes without crossing national frontiers… For humanitarian reasons these displaced people should be considered as refugees in the same way as those formally recognised by the Convention because they are victims of the same type of violence.

A complex reality

The bewildering array of definitions and terms used to describe people on the move mirrors the complexity of modern displacement: refugees, asylum seekers, voluntary economic migrants, survival migrants, undocumented migrants, boat people, stateless people, IDPs (internally displaced persons)…

The determination of official refugee status has become increasingly complex too. A person recognised as a refugee in Africa may not qualify for protection in Europe. Many are granted subsidiary forms of protection because although they manifestly cannot return home, they do not fit the criteria outlined in the Convention. Others do not qualify for, or cannot access, protection at all even if they need it and are 'invisible' to the international community, which has demonstrated a systematic inability to address their needs properly.

Some academics refer to the broader category of forcibly displaced people – barring IDPs – as 'survival migrants': people fleeing an existential threat to which they have no domestic remedy. The exodus of around two million Zimbabweans to countries in the Southern African region between 2005 and 2009 exemplifies this concept; they fled for a combination of interrelated reasons – mass livelihood collapse, state failure, repression and environmental catastrophe.

For many, emigration was the only available survival strategy. Yet the refugee recognition rate in South Africa, where many headed for, stands at less than 10%. This is no isolated case: elsewhere, many Congolese, Somalis, Haitians, Afghans, Iraqis and others have had the same experience.

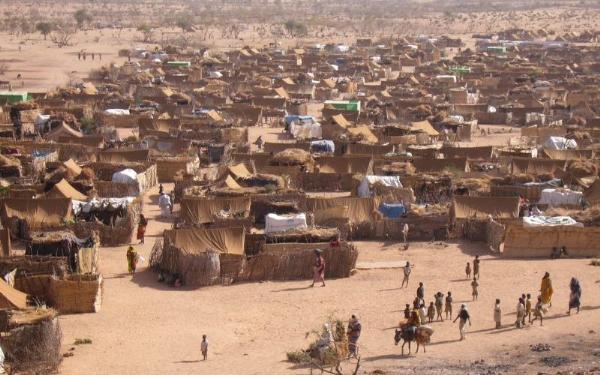

Some 26 million IDPs also fall through the protection net of the Convention. Their plight has been addressed to some extent by the global development of Guiding Principles that have led to the negotiation of regional treaties. The institutional response takes the 'cluster' approach whereby different humanitarian agencies are responsible for meeting one or other needs of the IDPs.

Another growing concern outside the scope of the Convention is the number of people adversely affected and displaced by climate change and other environmental factors: drought, land degradation, natural disasters…

New challenges

The Convention may also be seen to be out of touch with formidable challenges facing people on the move today. More than half of the world's refugees live in urban areas; often unregistered and undocumented, they constantly face protection risks, among them detention, deportation, exploitation and xenophobia.

Indeed, chief among the challenges is growing hostility in a world where, as Fr Nicolás said in his anniversary letter, ‘many are closing their borders and their hearts, in fear or resentment, to those who are different.’ This attitude is reflected in laws enacted with the express purpose of restricting access to asylum procedures and with extremely low thresholds for exceptions to the principle of non-refoulement, together with reinforced detention regimes. Detention of asylum seekers continues to cause great suffering worldwide. JRS Europe research reveals that almost anyone who is detained is likely to suffer from severe depression and deterioration to their wellbeing.

The shrinking access to protection is also due to heightened national security concerns, which are balanced against and often outweigh refugee rights. Sometimes, this has meant literally closing the border to asylum seekers, a hostile approach illustrated in the treatment of 'boat people'.

Risky sea travel by undocumented migrants has increased in recent years: often they are intercepted and turned back or denied landing or detained and abused when they have landed. And yet, when they manage to gain access to territory and asylum processes, a large percentage of asylum seekers who come by boat are granted protection.

Evolving the Convention's principles

The refugee protection regime built around the Convention remains as important and relevant as ever, but since the world no longer resembles the Europe of 1951, supplementary measures are necessary to ensure that de facto refugees get protection and assistance as part of a comprehensive framework.

Alexander Betts and Esra Kaytaz, from the University of Oxford, underline two core elements in a 2009 paper entitled ‘National and international responses to the Zimbabwean exodus: implications for the refugee protection regime’, which was published in a UNHCR series, New Issues in Refugee Research. The first element is a normative framework based on a multilateral agreement governing the subsidiary protection of those who fall outside the remit of the 1951 Convention. This framework would draw upon states' existing commitments under international human rights law. To date, the practice of granting subsidiary protection has been ad hoc and varying radically across countries, leaving significant protection gaps. The second element is an institutional framework that lays down a clear division of labour; a collaborative agreement to share responsibilities between relevant actors such as UNHCR, the International Organisation for Migration (IOM), and the International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC).

The 1951 Convention has saved the life of millions of people over the years. We hope that the 60th anniversary of this worthy instrument will serve to shore up the international protection regime through the reaffirmation and practical evolution of its principles.

After all, as the Vatican says in its 1992 paper, ‘the States who signed the Convention had themselves expressed the hope that it would “have exemplary value beyond its contractual scope”.’

Amaya Valcarcel is the Advocacy Coordinator for JRS International .

More for Refugee Week:

![]() Pray-as-you-go’s Refugee Week retreat

Pray-as-you-go’s Refugee Week retreat

![]() ‘Refugee Week: 60 Years of Contribution’ by Louise Zanre on Thinking Faith

‘Refugee Week: 60 Years of Contribution’ by Louise Zanre on Thinking Faith

![]() ‘Freely have you received, freely give’ by Bandi Mbubi on Thinking Faith

‘Freely have you received, freely give’ by Bandi Mbubi on Thinking Faith![]() ‘Malta: An island of refuge’ by Grant Tungay SJ on Thinking Faith

‘Malta: An island of refuge’ by Grant Tungay SJ on Thinking Faith ![]() JRS International

JRS International![]() Refugee Week 2011

Refugee Week 2011