Today marks the beginning of Refugee Week, 20-26 June, which this year will celebrate ‘60 Years of Contribution’ to the protection of refugees since the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees. Louise Zanre, Director of Jesuit Refugee Service UK, begins Thinking Faith’s series for Refugee Week by asking why a change in popular opinion about refugees is needed now more than ever.

This year marks the 60th anniversary of the UNHCR 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees. The Convention and its subsequent Protocols are remarkable documents, proposing a human rights based protection mechanism for individuals with a well-founded fear of persecution in their own country (either of origin or of residence) due to race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership of a social group.

The documents are not perfect and are very much a product of their time. They reflect the conflict between the very real memories of the horrors of the Second World War, the Holocaust and the lingering refugee camps in Europe from that time, and the new reality of world politics with the Cold War in its infancy.

The focus in legalistic terms is on individual persecution, not on generalised situations of violence or human rights abuses; the Convention also takes no account of other compelling reasons someone might flee, such as natural disasters or war.

Nevertheless, since then millions of people have received protection around the world, tens of thousands of them in the UK. Unsurprisingly, therefore, this year Refugee Week (20-26 June 2011) is taking as its theme, ‘60 Years of Contribution’. Refugee Week is an annual, awareness-raising and celebratory event in the UK, promoting a positive message about refugees.

The positive message is much needed. Over the last few weeks there have been major stories in the media, which have played to the negativity that so often characterises popular opinion on refugees, over the issue of a so-called ‘amnesty’ from which hundreds of thousands of ‘failed asylum seekers’ were supposed to have benefitted. Readers of Thinking Faith may recall the recent article on the issue by Austen Ivereigh.

I have worked at Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) UK for over ten years. It sometimes feels an awful lot longer, especially when I am confronted by negative, damaging and sometimes downright ridiculous stories about asylum seekers, refugees and migrants. It is with a sort of grim amusement that I recall news stories from 2003 claiming that asylum seekers were stealing the Queen’s swans to eat, or those from 2009 claiming that a deportation of an ‘illegal immigrant’ was stopped because he had bought a pet cat. In the former case, a small group of people had been caught cooking a duck and there were a couple of dead swans near them. A throw away line about the numbers of swans in the London area being in decline suddenly became an assumption that there was a self-evident link between asylum seekers, a contempt for the protected status of swans and theft. In the latter case, little was mentioned at the time about the fact that the cat owner had been living with his partner for four years and so under the immigration rules at the time was entitled to stay in the UK, whether or not they had bought a cat.

The vast majority of the negative stories that we see and hear in the media are the result of a form of shoddy journalism, which cares more about cheap sensationalism than the truth. Admittedly the truth can be more difficult to tell – immigration to the UK whether for economic reasons or to seek protection from persecution is a difficult and complicated subject, fraught with high emotion and misconceptions.

But the misinformation arising from such negativity is ultimately damaging to the fabric of our society. A fear of a sudden ‘amnesty’ for around 161,000 people and the resulting pressures on our country and our economy denies the fact that these people are already here and have been for many years, in some cases over a decade. It denies our shared humanity and, appallingly, denies the injustices these people have faced in their daily lives because of the failings of our systems and processes. The real scandal is not that 161,000 people have been given permission to stay in the UK, but that so many have had to wait so long for any effective decision-making process in their cases and that while they have waited the vast majority of them have had neither recourse to public funds nor permission to work. The scandal is that we continue to think as a nation that it is acceptable to leave people destitute and to waste their lives.

I know from our work at JRS that a whole new backlog of asylum cases is building up: people who feel they have not had a fair hearing (partly because they have not had effective legal assistance due to legal aid cuts), who have been refused asylum in the UK, who have not been removed by the government and who are unwilling to return to their own country voluntarily as they fear persecution. Some are from countries to which the UK cannot remove them forcibly as those countries have been declared unsafe for forced removals (such as Zimbabwe). They again are being left with no permission to work and no recourse to public funds.

They are destitute – in the true sense of the word. The word destitute comes from the Latin destituere, which means to abandon. As a nation we have abandoned and ignored them. We have denied their presence among us. We have shamefully left them open to exploitation and risk, increasing their vulnerability.

I attended recently a conference for ex-detainees, men and women who had been detained (some for weeks, some for years) in Immigration Removal Centres. The conference had been organised by the Dover Detainee Visitor Group. I had been asked to lead one of the workshops. One of the young men present asked, ‘Why do they hate us so much in this country?’ It is all too easy to see why he would ask such a question, given what he had seen in the media and given how he himself had been treated. All I could answer was: ‘Many of us don’t hate you.’ He, however, could only see the hatred and he was hurt.

There are so many good news stories out there: the students doing well at university (having fundraised from charities to cover their tuition fees) despite not knowing from one day to the next where they might be living next week, where they will find food or money for the bus fare to get to their lectures; finding a family member thought dead while walking through a market in London; falling in love; starting a family; getting a job after being given permission to stay in the UK; moving into a first real home after years of sofa surfing and homelessness; coming to terms with bereavement and grief or disappointment in life; learning a new language.

They are not widely publicised. They are all modest stories and experiences, and could be shared by any one of us. But that is the point, really. Rather than sensational, all of these lives – and ours – are both ordinary and at the same time special. And all of us can be hurt by an unkind remark, by a misrepresentation of the truth, by being made to feel unwelcome.

Over the years I have met nurses, doctors, scientists, engineers, businessmen and women, tailors, farmers, parents, students, children, teachers – all of them here seeking protection.

All of these modest experiences, all of the skills and talents brought by the asylum seekers and refugees enrich our society – or would if we would only allow them to share them with us.

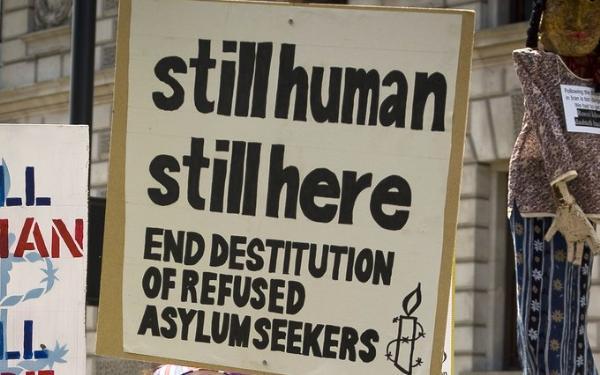

Until 2002 asylum seekers in the UK waiting for a decision on their application for more than 6 months had the right to work; now, an asylum seeker who has not had a first decision in his or her case within 12 months can apply for permission to work. If granted such permission, employment is normally restricted to ‘shortage occupations’ for skilled migrants. Many of us in the voluntary sector have campaigned through the Still Human Still Here coalition for the grant of permission to work for asylum seekers after 6 months if their cases have not been concluded or if they have been refused and cannot be returned to their own country through no fault of their own (such as the suspension of removals to that country).

This is essential for the dignity of the individuals and to keep them skilled or to help develop new skills. But it is also essential as a counter to claims that they are ‘scroungers’ and do not contribute. And – of no less importance – the more people who get to meet asylum seekers and refugees every day and who get to know them, the fewer there will be who automatically believe every negative thing reported about them.

If you do nothing else during Refugee Week, please take a couple of minutes to support the Still Human Still Here campaign by contacting your MP and asking him or her to support the policy: www.38degrees.org.uk/permission-to-work. Further information about the campaign is available at http://stillhumanstillhere.wordpress.com

Louise Zanre is Director of the Jesuit Refugee Service in the UK.

More for Refugee Week:

![]() Pray-as-you-go’s Refugee Week retreat

Pray-as-you-go’s Refugee Week retreat

![]() ‘Freely have you received, freely give’ by Bandi Mbubi on Thinking Faith

‘Freely have you received, freely give’ by Bandi Mbubi on Thinking Faith

![]() ‘The UN refugee convention: still valid?’ by Amaya Valcarcel on Thinking Faith

‘The UN refugee convention: still valid?’ by Amaya Valcarcel on Thinking Faith![]() Refugee Week 2011 website

Refugee Week 2011 website![]() Still Human Still Here campaign website

Still Human Still Here campaign website