In a letter from one of his many visits to Canada, Jean Vanier mentions a meeting with a prisoner in a Quebec prison. The incident isn’t afforded much space in the letter – only three sentences record it:

I also saw Réal Chartrand there. He looked well. When we met it was like two brothers seeing each other again.

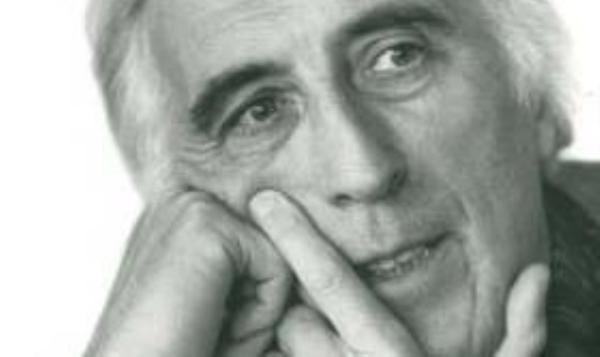

What the letter doesn’t explain is that the man whom Vanier meets was on death row for the murder of a police officer. Two men, one a murderer, the other an internationally acclaimed figure, meet ‘like two brothers’: this meeting encapsulates the spirit of the hundreds of letters contained in Vanier’s latest book, Our Life Together: A Memoir in Letters. It is a meeting between two humans, one of them an outcast, which takes place at a deep enough level to bypass the social structures, in this case the walls of a prison, that exist between people.

The letters in this book stretch from August 1964 to May 2007, over forty years of the growth of L’Arche and Faith and Light, the two networks founded by Vanier for people with disabilities, particularly those with learning disabilities. The letters root the growth of these two groups into the space and time of recent history. We hear of the unrest and desire for justice in 60s France, the context for the beginnings of the first L’Arche house; then through the following decades Vanier writes letters from the underside of political traumas – in India during the Bangladesh Liberation War, in Beirut in the late ‘80s, in Eastern Europe as the Berlin wall fell, September 11th and its aftermath. The letters also situate the organisations’ growth within Vanier’s life: his father and then mother’s deaths, the different phases of his life, from an energetic, searching man in his thirties to his gradual slowing of affairs in the later letters (Vanier turns 80 this September).

What emerges is how radical L’Arche in particular was, and is – radical “in the sense of the word that means ‘touching the roots’, the roots of our humanity”. Throughout the years of letters, the theme surfaces of living in community with the poor and rejected as a form of divine folly. Vanier writes of the modern world as one that privileges efficiency, productivity and power, one in which those who have not been called to full autonomy are pushed to one side. Many of the countercultural movements of the 60s reacted against this viciousness, but L’Arche and Faith and Light stand out as flourishing successes where many others have faded. Where the groups encounter difficulty, we find Vanier writing of committing himself in need to the Holy Spirit. The failures are recorded with authenticity and sadness – the death of a man in Bangalore due to a lack of supervision, or those who were unable to stay in the L’Arche houses and returned to psychiatric hospitals – but are enclosed in the rhythm of hope and prayer that energise the communities.

One of the places that stands out in the letters is Calcutta. What comes across in the letters is Vanier’s amazement at the extent of poverty and inequality and the depth of humanity that he encounters. He is honest about his own weakness, which is humbling to read:

It is so easy to reject the poor. So many times I have done it simply because I did not quite know what to do. It is easy to reject someone begging for money to buy a coffee and yet we easily stop and have a coffee ourselves when we really do not need it… It is easy to speak about Jesus, Jesus in the poor; but to go out into the streets and come face to face with people in rags, people with empty stomachs, is another matter…Pray that Jesus may keep me continually in anguish in front of the poor.

In another letter, he exclaims in frustration, “we are all so mediocre, so easily frightened”. The revelation of his weakness in these letters make them even more challenging to the reader: we can’t ‘dismiss’ Vanier as a saint, far above our human abilities; he is clearly ‘one of us’, but has abandoned himself to God to such an extent that his actions appear blessed.

This spirituality of abandonment, which Vanier explores more explicitly in other books, is apparent in the pleas that come at the end of most of the letters. From the early request for “birdcages and bicycles” to later requests for funding and prayer, it is clear that L’Arche and Faith and Light are sustained by the manifestation of God’s grace in their supporters. In a memorable phrase, he writes of “grafting each day onto Jesus”, a mindset born out of his love for weakness and smallness. Elsewhere he writes of the importance of being present with and for our neighbour. The paradox of being healed by those who we as society have rejected is something that is hard to feel the truth of if the experience has not been undertaken (as Pope John Paul II tells Vanier, it was only during his years of illness that he understood that message) – and it has echoes in the writings of the educator Paulo Freire and the novelist Ben Okri. The length of time covered by the letters allow the reader to witness the growth of this wisdom.

The relationship of this book to Vanier’s many others is an interesting one. Our Life Together is not, as he notes, the story of L’Arche (see Jean Vanier and L’Arche: A Communion of Love), nor is it an in-depth exploration of his spirituality. It is significant that his memoirs, which for so many other writers become an attempt to secure their version of their life-myth, is delivered in the form of letters: so often he writes of the importance of relationships between people as being central to God’s word. For those new to Vanier’s work, the book isn’t the best introduction: the weight of letters makes it more effective to read a section at a time, or to dip into a time period or place (something that the very useful index makes possible). However, those who have spent time with Vanier’s beliefs and work before will find it a beautiful addition to his life.

The reviewer, Nathan Koblintz, will be the 2008-9 IYLN Global Young Leaders Scholar, based at Blackfriars Hall, Oxford.

![]() Find this book on Darton, Longman and Todd's web site

Find this book on Darton, Longman and Todd's web site