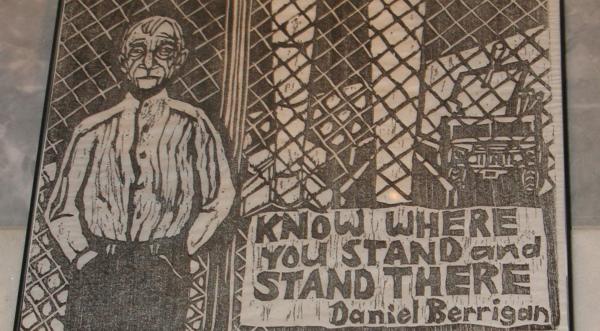

American Jesuit Daniel Berrigan died on 30 April 2016. As well as being an influential anti-war activist, he was a celebrated poet, and Emily Holman has relished having the opportunity to ponder Berrigan’s words in recent months and reflect on ‘the closeness of poetry and life’ that he communicated so creatively. In his poems we journey into and through darkness, are challenged by encounters and, above all, are guided by the hand of God.

Death can be serendipitous. I hadn’t heard of Daniel Berrigan until he died and Christian and secular media exploded with articles about his life and activism. Not having grown up with the frames of reference that surround the Roman Catholic tradition, even the most renowned of Jesuit heroes like Ignatius of Loyola or Francis Xavier weren’t figures I had heard of. I knew of Jesuits in a very childlike and immediate sense: because they ran the best secondary school in Lebanon, five minutes away from the village I lived in as a child. I knew that a Jesuit priest had married my parents, and that the Canadian and French Jesuits who had made the Society of Jesus famous in Lebanon were close family friends, and used to wind down with wine and cigars in my grandmother’s garden before she died. As I grew older I learnt a tiny bit more about Jesuits, mainly because Gerard Manley Hopkins was one. But it’s only in the last few years that I’ve come to encounter Jesuits in a realer sense, and that I’ve learnt about the tradition of the vocation and its meaning. My experience is still very nascent. Coming across the poetry of Daniel Berrigan, thanks to the publicity surrounding his death, has been one of the delights of new encounter.

There’s a beauty in freshness. The first poem I read was ‘A Dark Word’ (read it here), which was one of three Berrigan poems published in the April 1964 issue of Poetry magazine. The other two are good, too, complex, they call for more attention, and yet I kept – I keep – coming back to this one. It grapples so beautifully with the interplay between poetry and life: with the point of poetry, with what poetry is. Its first line reads: ‘As I walk patiently through life’. It’s such a slow, contemplative opening to a poem. It might be Wordsworth. And then a slight disruption: ‘poems follow close’. They have to, is the implication; there’s no other way. Poems are the deciphering of life, it seems: a way of coming to know, a mode of encountering one’s own experience. Yet the third line turns and twists again: poems are blind and dumb, silent and unseeing, stoppered somehow. Is it that they express, without perceiving? Are poems unspeaking symbols? ‘Blind’ and ‘dumb’ are words that threaten a narrowing of sense-experience; so what is it that enables poetry’s ‘agility’? Because these poems follow, don’t forget, wherever the poet walks: they’re his shadow, the mind’s dark overflow. There is an inevitability to them, and to the writing of them, which implies that, despite their imperfection and darkness, the poems are doing important work. It’s the poems that allow the walking to be patient. Were it not for these close-by poems, these alert markers and makers of experience, that opening line would be very different.

And Berrigan goes on: ‘The poem called death / is unwritten yet.’ It’s as if once an event comes, so too does a poem. Life will end, and there will be wisps left, shadows and ghosts, the abrupt end of a last line followed by a blank page. Does anyone ever know that the last thing written will be the last? Berrigan supposes it here, knowing that that will one day be the reality, and that someone, browsing his book, will come to the end, and close it shut. Reading this poem reminded me of a strange sense I’ve had recently reading Hopkins’s journals. He’s writing about Oxford, often, where I study; at other times he writes about St Beuno’s in North Wales, now a Jesuit spirituality centre. Reading him I feel the close echo of another life intimately. It’s a life full of what fills mine, what fills everyone’s: passionate care for the responsibility of being alive, passionate fear about that responsibility. Hopkins watches time passing and comments on it, marking it, and tries to live well. Writing helps. His entries are about trees and flowers, daily patterns, a strong wind, a visitor to a quiet place. Many days are unmarked. But what is the marking for? Why do we do it, this recapping of the day’s weather or the minutiae of moods? Why do ‘poems follow close’? When I close Hopkins’s diaries I wonder if he ever thought of other people reading about his daily thoughts 150 years after they occurred and feeling settled and calmed, and ready to go on, because, however briefly, they’ve been steadied.

Berrigan thought about it. He thought about his poems being read. Behind everything else in his continuingly resonant poem is the purpose of God. It is troubled, not easy; it feels complex; and the poet isn’t complacent. It’s significant that the hands that are purposeful like God’s are closing a book: it isn’t a metaphor that opens; it isn’t pacifying. But the hand is there.

After I read ‘A Dark Word’, I did what, as an Oxford student, I am lucky enough to be able to do. I called up all the Bodleian Library’s holdings of Berrigan’s work. So each afternoon in the library, working on my thesis, I have a break with some of Daniel’s poetry. I haven’t been struck by all of it – whether through inadequate focus and attention or tiredness or just a non-fit of poem to person. But I’ve loved a lot of it almost instantaneously. My favourite volume, of those I’ve read, is Encounters. The book is in two parts. The first is a series of meetings with figures from the bible and Christian tradition, including Eve, Abel, Isaac, Christ, Mary, Lazarus, Apostles, Saints Stephen and John of the Cross. In one, the Mary poem, is a line pertaining to what I’m beginning to think of as a Berrigan-theme: ‘Poems, like life, come to a dark mood’. There’s the word again, ‘dark’, and again the closeness of poetry and life. And it’s the poems that are dark, just as they are blind and agile.

The second part of Encounters offers meetings of another kind. Some are grounded in place, in Florence or Chartres. Some are meetings of thought, or image, or challenge, or task. ‘Heart grows wakeful for responsibility’. This is an experience at the centre of what it is to be human. God’s purpose, and ours – those are what we seek. Reading these poems has been a process of knowing the experience of that seeking.

I still know very little about Daniel Berrigan. But I’ve felt vividly the gift of knowing that comes with poetry. My stomach has twisted as I open a page at random in the Selected and New Poems edition of 1973, to see the opening stanza of a poem entitled ‘Abraham’, which comes from Encounters:

To see my small sonrunning ahead: pausing above a flower,bringing to me some trifle of hedgerowwearying, sighing, seeking my handThe scene and the mood are instantly present. The child’s enthusiasm and eagerness are felt, and then his childlike tiring, his need for the parent he trusts above all else, quiet and assumed; and behind those moods is that of the watching father, wretched, being torn with pain. Heart painful with blame, as Ted Hughes has it in his Oresteia. Later in that poem God’s hand features again. ‘I am sift of dust / in that Hand unmercifully blown / through mountain passes, a consummation // no nightmare of mine had groaned’.

The final poem in Encounters, not included in the Selected and New, is ‘This Book Bears’. It reminds you that poems are written to be read: that they provide encounters of their own. They’re a way of meeting – a very different kind of meeting to that which might take place face to face, though, if one is lucky, the face to face meeting might be as meaningful as the meeting in poetry. The book, Berrigan tells us, bears, ‘like a good voyager, marks of passage: / to proclaim, being loved / and led by hand through time, a life between the lines’. There’s the connection of writing and living again, and of writing and being loved. It’s Berrigan’s own life between the lines in this poem, from 1960, and he gives the sense in that stanza of having reached a conclusion, of having found rest. There’s the remainder of the poem to unsettle that rest, of course, not to mention ‘A Dark Word’ of four years later – let alone the life itself. Yet rest found, for however fine and fleeting a moment, is rest. I’ve found rest in this man’s poems. And I’ve been glad to have come to learn a sense of the man through his poetry before anything else. It’s rare, with contemporary figures, and quite a gift.

Emily Holman is studying for a doctorate in literature at the University of Oxford.