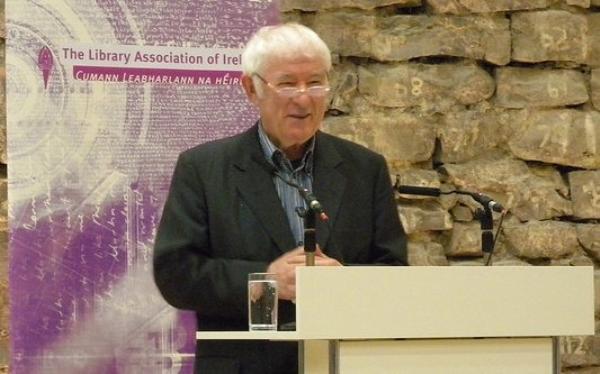

On 30 August 2013, news of the death of Nobel Prize-winning poet, Seamus Heaney, was met with sorrow around the world. He was universally admired for his kindness as well as for his poems, which ‘gaze into the reality of the world and see its mystery’. On National Poetry Day, Edel McClean pays tribute to the life and work of a man whose death, according to his fellow poet, Don Paterson, ‘seems to have left a breach in the language itself’.

It is hard not to be amazed that the death of a poet, of all things, made front pages around the world five weeks ago. Few contemporary writers have been held in such united, unreserved admiration as Seamus Heaney. We can expect a poet with poet friends to have beautiful things said about him after his death. Here we are not disappointed – Don Paterson wrote that, ‘the death of this beloved man seems to have left a breach in the language itself’. People who had never met him spoke of being stunned and heartbroken at the news of his death, finding themselves in tears watching his funeral. It is not just Heaney’s poetry that caused this deep emotional response, but also the man himself. He counted among his friends Bill Clinton, members of U2, the owner of the forge mentioned in ‘Door into the Dark’, even the cooks and cleaners of Harvard. There is little question that he related to all of them with the same open-hearted goodness. Given the cynicism with which many people regard those in the public eye, Heaney managed to wear his fame lightly and warmly, and to remain loved and respected across the globe.

It is in Ireland however, and particularly in his native North, where the sense of loss is most palpable. He was one of our own, our heart and our conscience. The former president, Mary McAleese, a fellow northerner and personal friend, spoke of ‘the genius of his poetry which made us so much prouder and taller and proud of ourselves through him’. Heaney’s was a voice of kindness and unhurried reason, who spoke his words of poetry in the cadences of the cattle dealer’s son, without any hint of condescension. He had the common touch, not driven by some relentless public relations unit, but by ordinary, common, human decency.

Born in 1939, Heaney was reared in rural simplicity, an ‘intimate, physical, creaturely existence’ [1], and would have continued to live such a life but for the freeing impact of the 1947 Education Act which allowed access to secondary education for a generation who would otherwise have been excluded. He remained ever grateful for that education, recognising that:

Young heads that might have dozed a life away

against the flanks of milking cows were busy

paving and pencilling their first causeways

across the prescribed texts….

… intelligences

brightened and unmannerly as crowbars.[2]

My first encounter with Heaney was hearing my sister reading, appropriately enough, the first poem from his first collection. I listened to the lines and instantly heard what Heaney described:

Under my window, a clean rasping sound

When the spade sinks into gravelly ground [3]

Later, at school, my wonderment only increased that a poet could capture so cleanly sounds of my own experience and show me something more in them. Heaney was my first introduction to truly great poetry; his was the first poetry I loved enough to learn by heart, the first poetry that would become a reference point for my life. This was a poet who, like me, lived among green hedgerows scattered with blackberries, who was aware of the intimate smell of mud and grass and briars, the sounds and touch of animals, the rhythm of farming family life. That poetry formed of these elements existed in published form seemed a miracle in itself. Reading ‘Broagh’, which mentioned ‘that last/ gh the strangers found/ difficult to manage’ [4], was to feel on the inside of a poetic heartland, rather than lost in a provincial periphery.

In Northern Ireland, however, Heaney was much more than a ‘relevant’ poet for youngsters. He provided a soundtrack for the years of the euphemistically named ‘Troubles’. Through those years of violence, the images being beamed out of Northern Ireland showed vitriol and brutality, hard lines and a murderous lack of nuance. The voices heard in Britain were the voiceovers for Sinn Féin or the furious, air-pounding words of Ian Paisley. It was a relief, then, to turn on the radio to hear Heaney’s voice, marked by consideration and deep sensitivity.

Growing up in rural Derry in the 1940s and 1950s, he knew well the tinderbox of inequality that sparked the Troubles. He did not turn his face or his pen away from his own political realities, yet was distressed by the violence that was used to force the change so deeply needed. He knew better than anyone the challenges of finding and speaking the right word: how to be true to self without condoning what was wrong; how to avoid teetering into bigotry on one side and platitudes on the other. He wrote of the ‘harrowing of the heart of Northern Ireland’ where, with the truth of daily news of yet more killings, ‘people settled in to a quarter century of life-waste and spirit-waste, of hardening attitudes and narrowing possibilities that were the natural result of political solidarity, traumatic suffering and sheer emotional self-protectiveness.’ [5]

Later, as the ceasefires took hold, his words were used by Mary McAleese and by Bill Clinton. In the heartbreak following the Omagh bombing, his lines from ‘The Cure at Troy’ gave words to a hungering and heartbroken people:

So hope for a great sea-change

On the far side of revenge.

Believe that a farther shore

Is reachable from here.[6]

This was no foreign voice, but a kind voice that resonated in the homes of quiet kindness that mark Northern Ireland more than any violence. He may famously have quipped, ‘Be advised/ my passport’s green/ No glass of ours was ever raised/ to toast the Queen’, but his fundamental decency and commitment to a different reality meant that he sat at the same table as McAleese and gladly raised his glass on the Queen’s historic visit to Áras an Uachtaráin in 2011.

Poetry, for Heaney, was clearly a vocation. In his Nobel Prize acceptance speech he described how,

...for years I was bowed to the desk like some monk bowed over his prie-dieu, some dutiful contemplative pivoting his understanding in an attempt to bear his portion of the weight of the world… Forgetting faith, straining towards good works… I began a few years ago to make space in my reckoning and imagining for the marvellous as well as for the murderous. [7]

His work is, indeed, marvellous. He had a towering intellect and stepped deftly through Greek translation, knew his French, Latin and Gaelic, and had a wide-ranging interest in myth, folklore, history and politics. He is capable of dizzying, gravity-defying use of language. Dennis O’Driscoll wrote of Heaney’s ‘rare capacity to improvise sentences which are at once spontaneous and shapely, playful and profound, beautiful and true’. [8]

Many of his most loved poems rise out of his family experience – love experienced from parents, brothers, sisters, wife and children. Where so much contemporary culture chips away at regret and resentment, Heaney takes the road of gratitude, to see the decency and goodness in people, to rejoice in the simple graces of peeling potatoes with your mother, seeing your father walking on the beach with his ashplant cane, or flying a kite with your children. In a particularly touching poem he writes about the gentle domesticity of his aunt’s bread-making:

And here is love

like a tinsmith’s scoop

sunk past its gleam

in the meal-bin.[9]

Heaney saw the transcendent in the immanent, the intangible in the tangible. His poems are otherworldly precisely because they gaze into the reality of the world and see its mystery.

Heaney’s stroke in 2006 clearly took its toll, but his intellect was as bright as ever and his collection ‘Human Chain’ was admired for how his ‘playing with rhythm, pushing phrases and images as hard as they will go, offers the poems an undertone, a gravity, a space between the words that allows them to soar or shiver’. [10] His poem ‘Miracle’ recalls his precarious descent on a stretcher in a stairwell of a Donegal bed and breakfast in the minutes following his stroke. He plays the tale out as from the gospels, the man lowered through the roof to meet Jesus. For Heaney, though, the miracle occurs not in the final moments, in some crescendo to the story, but in the people who bear the weight of the one struck down:

Not the one who takes up his bed and walks

But the ones who have known him all along

And carry him in –[11]

You get a sense of the man held in grateful bewilderment to be carried by such people – the ordinary miracle of kindness. At heart his life was a simple one. He was born to loving parents, he took a wife and remained faithful to her all his days, earned a living, raised his children, was delighted by the birth of a granddaughter (‘As her earthlight breaks and we gather round/Talking baby talk’ [12]), cared about his friends and did his best to walk with integrity through the world. For all his use of the ‘squat pen’ of ‘Digging’ to dig his own furrow, he followed in his father’s footsteps in a life of simple decency. Here he was undoubtedly influenced by the Catholicism of his family and schooling which he never entirely shook off. In ‘Ten Glosses’ he writes of the rote Catechism answers he learned at school:

Q. and A. come back. They ‘formed my mind’.

‘Who is my neighbour?’ ‘My neighbour is all mankind’. [13]

Intended or not, he proselytised this message, so that the CEO of the charity Concern (of which Heaney had acted as a patron) said that those words, taken from Heaney, had become an unofficial motto of the organisation.

Heaney’s antennae seemed to be ever on the alert for those moments of transfiguration, those moments when something greater seemed to reach out and touch us or, as he put in ‘Postscript’, ‘catch the heart off guard and blow it open.’ [14] In this sense the power of faith, it might be said, is not unlike the power of poetry as he describes it – ‘the power to persuade that vulnerable part of our consciousness of its rightness in spite of the evidence of wrongness all around it’ [15]. His eyes caught those moments when that ‘vulnerable part’ came to the surface for air, and gave what he saw their due reverence. Such an attentiveness and alertness seemed to create a profound sense of gratitude which is glimpsed throughout his work. In his obituary of Heaney, Neil Corcoran tells of how, when pressed in an interview to choose an epitaph for himself, Heaney chose a line from Sophocles’s ‘Oedipus at Colonus’: ‘wherever that man went, he went gratefully’ [16]. It is his gratitude that may be one of his greatest gifts to us. While we mourn the passing of the man, we can be grateful for his writings which still grace our bookshelves or our Kindle. Both his life and his works provide a fundamental reminder of the goodness of life, the sheer exorbitant gift of it, encouraging us to ‘walk on air against our better judgement’[17]. As for the source of the gift, Heaney was not one for cheap words, and his thoughts on encountering the extraordinary are characteristically cautious and carefully weighted:

There’s a double sensation of here-and-nowness in the familiar place and far-and-awayness in something immense. When I experience things like that, I’m inclined to credit the prelapsarian in me. It seems, at any rate, a greater mistake to deny him than to admit him. [18]

Edel McClean is a member of the team at Loyola Hall Jesuit Spirituality Centre.

More poetry on Thinking Faith:

![]() ’Secular Psalms: Faith and Contemporary Poetry’ by Nathan Koblintz

’Secular Psalms: Faith and Contemporary Poetry’ by Nathan Koblintz![]() ’The Sermon and the Whisper’ by Nathan Koblintz

’The Sermon and the Whisper’ by Nathan Koblintz![]() ?Who’s Afraid of the Big, Bad Poet?’ by Gemma Simmonds CJ

?Who’s Afraid of the Big, Bad Poet?’ by Gemma Simmonds CJ ![]() Brian McClorry SJ reviews R.S. Thomas: Uncollected Poems

Brian McClorry SJ reviews R.S. Thomas: Uncollected Poems

![]() Nathan Koblintz reviews Kristin LeMay’s I Told My Soul to Sing: Finding God with Emily Dickinson>

Nathan Koblintz reviews Kristin LeMay’s I Told My Soul to Sing: Finding God with Emily Dickinson>

[1] Heaney, Seamus., ‘Crediting Poetry: The Nobel Lecture’ (1995) in Heaney, S., Opened Ground (London: Faber and Faber, 1998).

[2] Heaney, ‘From the Canton of Expectation’ (1987) in Opened Ground.

[3] Heaney, ‘Digging’ (1966) in Opened Ground.

[4] Heaney, ‘Broagh’ (1972) in Opened Ground.

[5] Heaney, ‘Crediting Poetry’.

[6] Heaney ‘The Cure At Troy’ (1990) in Opened Ground.

[7] Heaney, ‘Crediting Poetry’.

[8] O’Driscoll, D., Stepping Stones: Interviews with Seamus Heaney (London: Faber and Faber, 2008).

[9] Heaney, ‘Mossbawn’ (1995) in Opened Ground.

[10] Tóibín, Colm, ‘Human Chain: A Review’ in The Guardian, 21 August 2010 .

[11] Heaney, ‘Miracle’ (2010) in Human Chain (London: Faber and Faber, 2010) .

[12] Heaney, ‘Route 110’ (2010) in Human Chain.

[13] Heaney, ‘Ten Glosses’ (2001) in Electric Light (London: Faber and Faber).

[14] Heaney, ‘Postscript’ (1996) in Opened Ground.

[15] Heaney, ‘Crediting Poetry’.

[16] Corcoran, Neil, ‘Seamus Heaney: obituary’ in The Guardian, 31 August 2013, p. 2.

[17] Heaney, (1995) ‘Crediting Poetry’.

[18] O’Driscoll, Stepping Stones.