Brian Mac Cuarta SJ describes how he came to uncover the story of a seventeenth century Jesuit martyr whose ministry to those in need led to him becoming known as the ‘father of the poor’.

Some years ago, I became interested in Irish people who travelled to Rome in the period of political and religious turmoil in the decades before and after 1600. One of these was Henry Piers (c.1567-1623), born of English parents who were landowners in County Westmeath. Together with a young Englishman, Henry travelled from Dublin to Rome in 1595. I edited the travel account Piers wrote on his return to Westmeath.[1] Then I was led to research another traveller, Francis Slingsby (1611-1642), from Cork in southern Ireland, whose parents likewise were English. After studies at Oxford, his father sent Francis to travel in France, from where in 1633 he moved on to Italy. Much to his father’s chagrin, Francis converted to Catholicism, and wanted to join the Jesuits. First, however, he decided to study at the Venerable English College, Rome, which he did in the years 1639 to 1641. Thereafter he joined the Jesuit novitiate in Rome, but died about a year later.

His Roman contemporaries felt there was something saintly about this convert from a far-away country. Just after his death, his Jesuit superiors asked fellow-students and those who knew him to write their impressions of this man. A collection of these testimonies, together with some letters to and from Slingsby, was the result. I am preparing these materials for publication. One particular testimony had left me puzzled for a few years now. In it, an English College student described how Francis approached him, and asked him to meet every week; with a view to helping both to grow in virtue, each man was to disclose the faults of the other. The writer indicated that over their two years together, he could find no real faults in Francis; Francis in turn would obliquely make a few gentle observations about his companion, drawing on the church father Cassian for words of advice for the young man.

Until recently I couldn’t decipher the name of the writer, given at the top of the page. I knew the first name was Charles, and the family name began with ‘B’. Then a few days ago, glancing over the names index in the published Responsa (or college entrance interviews) for the English College in Rome, I came across ‘Baker, Charles’. The interview summary indicated that Charles had entered the college in November 1638, aged 21, just three months before Francis Slingsby, so they were college contemporaries. All English College seminarians in Rome at the time used aliases, to protect them when they would return to England.

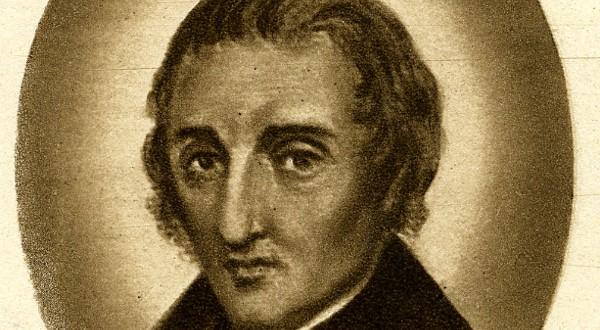

It emerged in the Responsa that this man’s real name was David Lewis (1617-1679), from Abergavenny in Monmouthshire, south-east Wales. His father was headmaster of the town’s royal grammar school where young David had studied. The family – there were nine children - were Anglican, though their mother, Margaret Pritchard, was Catholic. David’s uncle was a Jesuit, John Price (c.1577-1645), for many years based at Worcester. Probably through this connection, when aged fifteen, David travelled with another boy from Abergavenny to Paris. There he became a Catholic, through the ministry of an English Jesuit based in the city, and returned home. ‘For the love of religion and letters’, as he himself relates, David then left home a second time, and presented himself at the English College, Rome.

After ordination, he joined the Jesuits in Rome, and from 1650 was back in Monmouth, ministering to Catholic families, and gaining respect and trust for his pastoral zeal, especially among the poor, to such an extent that he became known as the ‘father of the poor’. For several decades he moved about without hindrance. However, in 1678-1679, the Popish Plot erupted, in which it was alleged there was a Catholic conspiracy to kill the king; it later emerged that the so-called ‘plot’ was without foundation. However, it led to a frenzy of anti-Catholic activity, in which several ecclesiastics were apprehended and put on trial. One of these was David Lewis, in Wales. He was tried and condemned on the testimony of perjured witnesses at the Monmouth assizes, then brought to Newgate prison in London, to be interrogated by Titus Oates, the ringleader of the anti-Catholic campaign; he was then returned to Usk, Monmouthshire for execution. He was hanged there on 27 August 1679, aged about 62. In a testimony to the respect in which he was held locally, at his execution the crowd tried to intervene, and they ensured that he died without the barbarity prescribed by law for those (like David Lewis) who had been convicted of treason. Friends in the crowd then took the body and interred it in a place of honour immediately outside the main door of the parish church, where it remains an object of veneration to this day.

In 1970, David was canonised as one of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales.

And so I finally learned the true identity of this student companion, and soul-friend, of Francis Slingsby, the subject of my research. I got a glimpse of their life as students in Rome, some forty years before David’s martyrdom. It was moving to see how they supported each other in seeking to grow in virtue, and to learn of the fruits in David’s long service of the people of Monmouth, and especially of the poor, and his simple yet heroic witness at life’s end.

Brian Mac Cuarta SJ is fellow in early modern history at Campion Hall, University of Oxford.

[1] Brian Mac Cuarta (ed.), Henry Piers’s Continental Travels 1595-1598 (Cambridge University Press, 2018).