Only five women are mentioned by St Matthew in his genealogy of Jesus, which we are exploring this Advent alongside Pray as you go. Two of the five are Rahab and Ruth, the mother and wife, respectively, of Boaz; and their inclusion reveals some startling truths about faith. David M. Neuhaus SJ asks what we can learn from these women, and from the context in which their stories are told, as we continue to pose the question, Jesus: Who Do You Think You Are?

The Gospel of Saint Matthew begins with the genealogy of Jesus Christ that takes us all the way from Abraham to ‘Joseph the husband of Mary, of whom Jesus was born’ (Matthew 1:16). In this supremely theological composition, Matthew weaves the new, ‘Jesus… who is called the Messiah’, into the fibres of the old, the generations of Israel before Jesus’s arrival. The text is read at Mass just before Christmas, tripping up many a priest who tries to get his tongue around the unfamiliar Hebrew names. However, those names veil some rather stunning surprises.

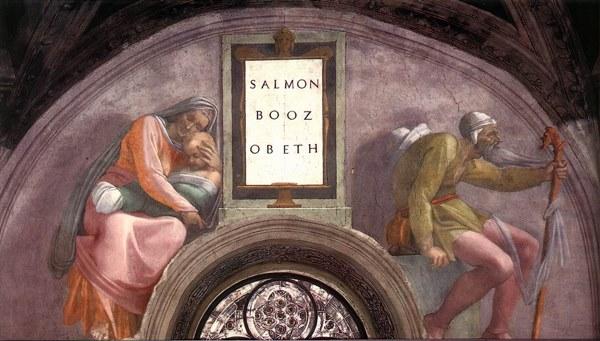

Among those many surprises, the one that always attracts my attention is the one hidden in the words ‘Salmon the father of Boaz by Rahab, and Boaz the father of Obed by Ruth’ (Matthew 1:5). The genealogy is a predominantly patriarchal affair: fathers having sons, from Abraham at the beginning, to Jacob, the father of Joseph, towards the end of the genealogy. The last surprise is that Jesus will be born of Mary, Joseph’s wife, whereas Joseph will be proclaimed a father who is not really a father by the angel who announces Mary’s pregnancy before Joseph has taken her into his home. The surprise of Mary’s role in the genealogy has been prefigured in the four other women mentioned in the text: Tamar, Rahab, Ruth and the wife of Uriah. Each of these women veils a surprise in the unfolding of the generations. Let us examine in more detail the double surprise of Rahab and Ruth.

Rahab the Canaanite appears in chapters 2 and 6 in the Book of Joshua (the Book of Jesus if we are reading our bible in Greek). Her name, ‘wide as a road’, indicates with no small degree of crude humour her profession: a whore. The two men sent by Joshua as spies to Jericho spend the night in her home. Alien men in a prostitute’s house would not normally arouse suspicion. However, the king of Jericho has been warned of their coming and, assuming that the foreign men would be found in Rahab’s house, he orders her to bring them out. She defies the king by protecting the spies and then surprises us even more when she professes her faith: ‘The Lord your God is indeed God in heaven above and on earth below’ (Joshua 2:11). Introduced as a whore, she reminds us now of Lot refusing to deliver up the two angels to the clamouring mob in Sodom, but even more of other saviour women in Israel’s history, both Israelite and foreign: the midwives in Egypt, Shiphrah and Puah, who save the Israelite male children (Exodus 1); Yocheved, Miriam and Pharaoh’s daughter, who save the child Moses (Exodus 2); and Zipporah the Midianite, who saves Moses from God’s wrath (Exodus 4).

Rahab’s faith will save her and her entire family. Jericho is slated for destruction and the Book of Deuteronomy has already informed us of the fate of the cities that the Israelites will conquer in the land: ‘As for the towns of these peoples that the Lord your God is giving you as an inheritance, you must not let anything that breathes remain alive’ (Deuteronomy 20:16). Therefore the great surprise in Jericho is not that Joshua orders the slaughter of every living thing – ‘The city and all that is in it shall be devoted to the Lord for destruction’ (Joshua 6:17) – but rather that Rahab and her family are saved: ‘Only Rahab the prostitute and all who are with her in her house shall live because she hid the messengers we sent’ (Joshua 6:17). Dare we hope that all the townspeople gathered in her home and were saved with her because of her faith, and that nobody died on the day the walls of Jericho fell because they all found refuge in the wideness of her house?

Rahab’s story of faith is only half of the surprise in the Book of Joshua. The other half is revealed in chapter 7, which tells the story of the Israelite Achan’s betrayal. We might have been tempted to believe that God’s election of Israel sets up a permanent and impermeable border between ‘God’s chosen’ and the heathens, but Achan’s story, immediately following Rahab’s, further illustrates that this is far from true. Parallel to the surprise of Rahab’s faith is the sad tale of Achan’s betrayal of faith.

Achan, son of Carmi of the tribe of Judah, an Israelite, takes part in the conquest of Jericho. God’s command to take no booty from Jericho is crystal clear: ‘keep away from the things devoted to destruction, so as not to covet and take any of the devoted things and make the camp of Israel an object for destruction, bringing trouble upon it. But all silver and gold, and vessels of bronze and iron, are sacred to the Lord; they shall go into the treasury of the Lord’ (Joshua 6:18-19). Achan steals from God and hides the booty in his tent. His crime will only be unveiled when the Israelites meet defeat in the next round of battle, trying to conquer the town of Ai. Abandoned by God, the Israelites are beaten back and Joshua (Jesus), crying out to God, is informed of the sin that has entered the people through Achan. Achan’s fate is the same as that reserved for Jericho. This sad tale of betrayal is echoed in the Acts of the Apostles (chapter 5) in the tale of Ananias and Sapphira, the first two to die after Pentecost because of their betrayal in stealing from what had been given to the Lord.

The parallel between Rahab and Achan drives home that God seeks fidelity and will not always find it among the ones who claim to be God’s chosen ones. Instead, faith will sometimes radiate from those places least expected, even the house of a Canaanite whore.

It is interesting to note that Matthew is the only biblical writer to tell us that Rahab was the mother-in-law of Ruth. In the Old Testament, they are seemingly unrelated. Ruth is not a whore but a Moabite, a member of a despised people. The Law of Moses states without ambiguity: ‘No Ammonite or Moabite shall be admitted to the assembly of the Lord. Even to the tenth generation, none of their descendants shall be admitted to the assembly of the Lord (…) You shall never promote their welfare or their prosperity as long as you live’ (Deuteronomy 23:3;6). These peoples, purportedly descended from the incestuous relations between Lot and his daughters (Genesis 19:37-38), tried to curse Israel on the way to the land (Numbers 22-24).

Ruth’s story follows the description of the darkness that falls on Israel in the land in the days of the Judges. Sin is everywhere in the last five chapters of the Book of Judges as the people is described as falling into idolatry and civil war, these being perhaps among the most violent chapters in the Bible. The oft-repeated refrain in these chapters also concludes the book: ‘In those days there was no king in Israel; all the people did what was right in their own eyes’ (Judges 21:25). The King of Israel, God, who had brought the people out of Egypt into the land of milk and honey, had been brutally booted out of the story by a people living in sin. Whereas they were chosen to proclaim the Kingdom of God by lives lived in faith, their choices had led them far astray.

The Book of Ruth opens with the evocation of the time of the judges. Ruth, the Moabite wife of an Israelite who has died, swears fidelity to her widowed mother-in-law, Naomi, and returns with her after the loss of Naomi’s two sons to their ancestral land of Bethlehem. As they set out, Ruth makes a profession of faith that has immortalised her as an ideal of faith for Jews and Christians: ‘Where you go, I will go; where you lodge, I will lodge; your people shall be my people, and your God my God’ (Ruth 1:16). The Moabite woman has not only been admitted to the assembly of the Lord, but she has become a model of faith.

This admittance into the assembly of the Lord despite what the Law states can only make sense if we realise that Bethlehem in the final chapters of the Book of Judges is the very epicentre of the darkness of sin. The priest that initiates the idolatry and the woman whose horrible death will provoke the civil war that rages in Israel are both from Bethlehem. How will God bring light into the world if the people God has chosen to be a light to the nations has chosen darkness instead of light? God needs a new Abraham, who is willing to leave ‘land, kindred and father’s house’ (Genesis 12:1), to open a way for God’s re-entry into history. God finds that new Abraham in Ruth the Moabite, who comes to dark Bethlehem radiating the light of her faith.

In Bethlehem, Ruth will begin a new life, marrying Boaz and becoming the great-grandmother of King David. Matthew tells us that Ruth the Moabite not only receives a new husband to replace Chilion, son of Naomi, but alongside Naomi, she receives a new mother-in-law, Rahab, the Canaanite whore, herself a shining light of faith.

The presence of Rahab and Ruth in the genealogy of Jesus should shock us at first: a whore and a Moabite. As we meditate on these two surprising women of faith during this Advent season, both unexpected radiant lights in the genealogy, let us be less quick to judge those who seem to be outsiders. Light can shine from the most unexpected places and if we let it, it will penetrate our darkness too.

Fr David M. Neuhaus SJ serves as Latin Patriarchal Vicar within the Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem. He is responsible for Hebrew-speaking Catholics in Israel as well as the Catholic migrant populations. He teaches Holy Scripture at the Latin Patriarchate Seminary and at the Salesian Theological Institute in Jerusalem and also lectures at Yad Ben Zvi.

Read more:

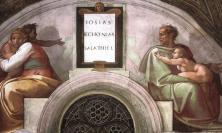

4. Jechoniah

5. Zechariah, Elizabeth and John

For further reflection, try Pray as you go’s Advent retreat, ‘All the Generations’. Listen >>