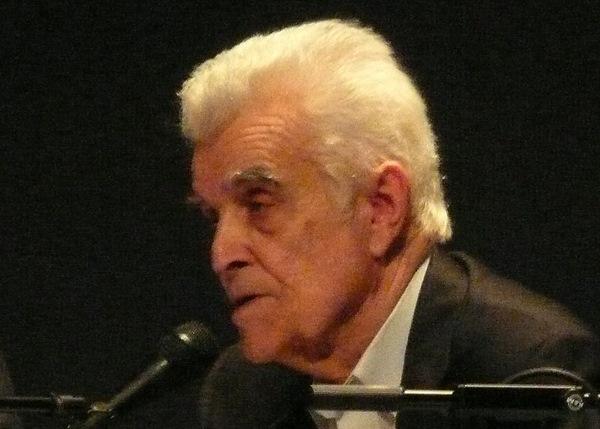

This week, we learned of the death of ‘the new Darwin of the human sciences’, René Girard. Michael Kirwan SJ, author of Discovering Girard, pays tribute to a deeply committed and humble Catholic theologian who declared that ‘violence is the heart and secret soul of the sacred’.

René Noël Théophile Girard was born in Avignon on Christmas Day, 1923. He died in California on 4 November 2015. He leaves behind Martha, his wife of 64 years, three children, and nine grandchildren. As one of the most important Catholic thinkers of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, he has left a precious intellectual legacy as ‘the new Darwin of the human sciences’, whose books offer a bold, sweeping vision of human nature, human history and human destiny.

The comparison with Charles Darwin is apt, as Girard’s work similarly sketches out human origins. However, it has a specific focus on the origins of human violence, which for Girard is tied up with the origins of all cultural forms, even – and especially – religion. In his most famous book, Violence and the Sacred (French original, 1972), he declared that ‘violence is the heart and secret soul of the sacred’. His work ever since has been a call, and a warning, to take seriously the dangerous proximity of religion and violence. As part of their evolutionary programming, human beings have a ‘fatal attraction’ to competition and rivalry (one may speculate whether this has anything to do with having to share a birthday with Jesus …), which, if unchecked, will lead to violence. The conflict he has in mind is often contained by and contained in religious practices: ‘sacrifice’, ‘penal atonement’, ‘holy wars’, ‘apocalypse’, and other practices oriented toward salvation. At the centre is the figure of the ‘scapegoat’, the victim who is marginalised, even exterminated, so that the community can survive.

Such a theory seems to be very ‘anti-religious’, and yet the thinker behind it was a deeply committed and humble Christian thinker. Girard returned to his Catholic faith in 1959, when he realised the importance of the scriptures in showing us the truth about the human situation, and what we needed to do about it. The gospels show us Christ as the Lamb of God who ‘enacts’ the place of the scapegoated victim, so as to expose once and for all the truth of ‘butchers pretending to be sacrificers’.

For many years his Christian commitment made Girard an unfashionable thinker in the secular academy, though his election in 2005 to the prestigious Académie Francaise indicates that his life’s work had received proper recognition. I would like to offer just a few personal memories. First of all, though his work was initially not well-received by the French Jesuits (it was unfavourably reviewed in 1972), the fruitful interaction with other Jesuits in the course of his career has been very important. Above all, we need to mention his close collaboration and friendship with Raymund Schwager SJ, Professor of Theology at the University of Innsbruck, as well as other members of that faculty.

Professor Girard was very grateful to to the British Jesuits for their hospitality to him during three visits to England. At the suggestion of Billy Hewett SJ, and at the invitation of Joe Munitiz SJ, he was invited to Campion Hall to give the D’Arcy lecture in 1996. A decision to switch the venue, from the Campion Hall library to the university exam school, was fortunate, as 200 people turned up to hear him give an extraordinary lecture on ‘Violence, Victims and Christianity’. Another highlight on this occasion was his first visit to Stratford; he has always maintained that the drama of Shakespeare (especially A Midsummer Night’s Dream) was inspirational for his theory of mimetic desire. His book on Shakespeare, A Theatre of Envy, remains a masterful introduction to his theory for an English-speaking audience.

The second of his two visits to Heythrop College was to receive an honorary doctorate from the college. While this was a splendid and gracious affair, it as clear that he was much more nervous about the ceremony of acceptance at the Académie Francaise a few days later. His good-humoured charm was evident throughout, if not always credible, as for example when he assured us that London was a more beautiful city than Paris! Though he was sardonic at times about academic life and its absurdities, he went out of his way to listen to young scholars giving papers at conferences and give them encouragement, something which I know from my own personal experience. During one conversation after I had started teaching at Heythrop, he asked me: ‘And do you enjoy it?’ I don’t remember what I said; but this remains the only time anyone has asked me that question.

The ‘immense intellectual holiness’ is conveyed by the attitude he showed toward his own theory: at times he was like an evangelical about his insights, but he was also capable of being playful, even offhand:

People are against my theory, because it is at the same time an avant-garde and a Christian theory … Theories are expendable. They should be criticized. When people tell me my work is too systematic, I say, ‘I make it as systematic as possible for you to be able to prove it wrong.’

Underlying this challenge is a serene confidence that the truth he is proclaiming is not after all ‘his’ truth, but the truth of God’s revelation, made available to us as a sign of our troubled times.

Girard is a thinker who combined an utter lack of self-importance with the boldest intellectual risk-taking. A Stanford colleague, Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht, declares that Girard is:

a great, towering figure – no ostentatiousness. … Despite the intellectual structures built around him, he's a solitaire. His work has a steel-like quality– strong, contoured, clear. It's like a rock. It will be there and it will last.

Michael Kirwan SJ is Head of Theology at Heythrop College, University of London. He is the author of Discovering Girard (Cowley, 2005).