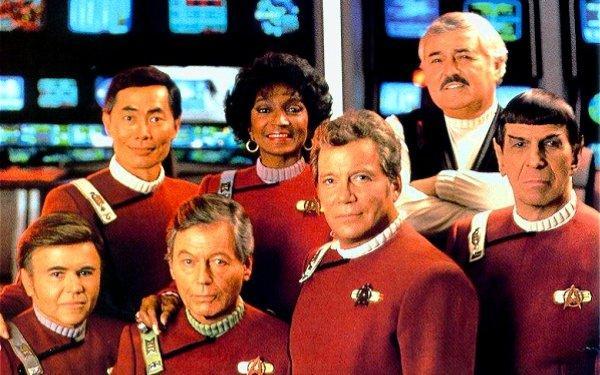

Simon Potter’s quest to find an example of prudence on the big screen took him to far-off worlds. In this instalment of our Lenten series, he describes how that virtue is a prominent feature of the voyages of the USS Enterprise. It is in the six original Star Trek films that he considers the prudent care of the crew for one another and for their mission to be most evident.

He might not have intended it to become the inheritor of the epics of the past, but Gene Roddenberry’s Star Trek firmly catapulted the spiritual and moral quests of Kirk, Spock, McCoy, Scotty and Co into that fourth category of Epic which follows Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey (primary), Virgil’s Aeneid (secondary) and Milton’s Paradise Lost (tertiary). Writer Ace Pilkington has drawn attention to the ‘theological pre-occupation’ of the original TV series, but I believe that it is in the six original motion pictures that the franchise expanded into moral density.

What exactly must a work of created art do to be epical? It must lift mankind out and up from the humdrum and show the human race as engaged in an enormous, long-running quest. Embedded within the sweep of theme must be tales of love, sacrifice, bravery and honour, and their corollaries: greed, xenophobia, personal aggrandisement. The form must underpin all with solemn power; in Paradise Lost, Milton uses vast verse paragraphs (often a single sentence), stately latinised syntax, remorseless decasyllables, extended similes, reference to the Classical past, and the display of polymathic learning – all of which mesh superbly with idea to bring about something ‘unattempted yet in prose or rhyme’. Thus, in its forms of wide-screen moving image and Dolby multi-channel sound, Star Trek must propel theme into lasting resonance in order to be epical. This it does, also with a display of prescient knowledge, signposting by quoted reference to a classical past (the sixth film, The Undiscovered Country has lines from Hamlet, Twelfth Night, Romeo and Juliet, Richard II, Henry IV: Part 2, Henry V, Julius Caesar, The Merchant of Venice and The Tempest) and enormous sets.

It is thanks to peerless special effects (several of the films using the resources of Industrial Light & Magic); grand, sweeping music (by James Horner and others); intelligently linked scripts which avoid too much self-referencing, but make, from 1979 to 1991, a coherent over-arching plot; and a sense of seriousness and reality in the cast, that the Star Trek movies get away with reaching far beyond their medium. Lucas’s overtly cartoonish Star Wars did not have the same flavour, nor did the dark and menacing worlds of Alien, Total Recall or Pitch Black – brilliant though they may be. Only Star Trek reaches the heights of grand epic.

The optimism inherent in the six linked Star Trek films goes further than Homer’s tale of Man and Gods at war over a citadel, further than the destined founding of Rome, further even than Milton’s desire ‘to justify the ways of God to Man’. In Star Trek there is, held out as the prize, the near-Godhead of the humanoid him/herself. We see it at the beginning when Commander Decker and Ilia merge together in the living machine that is V’ger; we see it at the end when the laying aside the hurts of the past is necessary for galactic shalom. The virtue most often on display to achieve such things is that of prudence.

Prudence, as a word, has several connotations – not all epical, heroic, nor even admirable. In its most strangulated (and British) sense, it conjures an emasculated cautiousness, a penny-pinching and timid fear of the future. Its Latin roots (prudens/providens) bespeak a wider show of good judgement, of worldly understanding of risk and the pitfalls that lie in front of the reckless. Such extremes are the very stuff of much of the character tensions in Star Trek. Who can forget the prudent warnings of Chief Engineer Scott? (‘I dinna dare push her any further, Captain. The di-lithium crystals’ll never stand the strain.’) Who can doubt the sober, considered advice of Mr Spock, emotionless Vulcan, whose research, restraint and experience so often saves the Enterprise and its crew from disaster? (‘I have calculated that we have seventeen minutes to reach the edge of the nebula, Jim. To delay now would be fatal.’) Who has not echoed ‘Bones’ McCoy’s exasperation at Jim Kirk’s urge for self-sacrifice? (‘Jim, as this ship’s doctor, I order you to lie down.’) And Jim Kirk? His is that resistance to stuffy, minor-key prudence which makes the grand leap of instinct or of intuition and, as McCoy grudgingly admits, brings ‘what you always bring – a chance of life.’ Key to all Jim Kirk’s final decisions is that larger prudential vision: the care of his ship and its 400 souls, and the wide mission of the United Federation of Planets – ‘To boldly go where no Man [or woman] has gone before’, to explore new worlds and new civilisations and to bring peace.

Paramount gave the veteran director Robert Wise the task of bringing the first film, Gene Roddenberry’s In Thy Image to the screen in 1979 (the title was dropped in favour of Star Trek: The Motion Picture, but tells what he intended). A vast cloud of energy with an unknown core is approaching Earth, destroying matter as it does so. Kirk & Co are sent to investigate and, as they approach it with prudence, Spock senses that it is more than mere matter. After Spock has deemed it prudent to ‘mind-meld’ with the probe that the alien vessel sends to the Enterprise, it is discovered the mysterious core is actually Voyager 6: sent out beyond the solar system by Man in the 1970s, it was found by a race of living machines and programmed to return to its Creator ‘with all that can be learned’. On its endless voyage, it learns so much that it achieves consciousness, and finding Earth contaminated by carbon life-forms (Man), it believes the prudent thing to do is to eliminate them and thus become one with the Creator. When it discovers that humans are the Creator, it yearns for union. With the highest prompt of providential action, Kirk’s second in command volunteers to become one with the conscious machine. Was this a vision of the next development of humanity?

Following lukewarm reviews which criticised the film’s funereal pace and excessive solemnity, its lack of a villain, and the enormous expense of production, Paramount exercised a different form of prudence and replaced Roddenberry with a new producer (Harve Bennett), brought in Nicholas Meyer as director for the first time, and slashed the budget for Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. A fine villain, Khan Singh, in the shape of Ricardo Montálban, was created; self-preservation (he has been exiled) and revenge (he blames Jim Kirk for the death of his wife) are his motives, but as Montálban noted, all good villains believe their reasons are right. Thus a personified corollary of virtuous prudence was created to provide tension. Further layering saw Kirk’s son, David, developing ‘The Genesis Project’ (originally an idea of Roddenberry’s), a technology which can create planetary life from the dust of a nebula. Leonard Nimoy (as Spock) was happy to agree that, in an act of selfless prudence, his character should die of radiation poisoning struggling to save the Enterprise’s warp-drive before the shock-waves of a newly-created planet in the Mutara Nebula cripple it. Spock’s burial-place is this new world. Nimoy expected the film to end the Star Trek revivals.

By 1983 it was clear that, after enthusiastic reviews, the franchise should continue, so Nimoy himself came back to direct The Search for Spock. It was decided that the TV series’ Klingons should be established as the opponents of peace and progress (eventually, by the sixth film, carrying both Nazi and Cold War identification overtly). The story picked up where The Wrath of Khan left off. The Genesis planet has developed life and Spock’s corpse has been reborn as a child from his tissue. He left his spirit in the brain of McCoy as he died, and the ship’s doctor has been struggling with a dual-personality ever since. Kirk deems it prudent to take the rapidly ageing Spock off the new planet to his home world, Vulcan, where his soul and body can be re-united before evil Klingon, Christopher Lloyd (overdoing it magnificently) can seize the Genesis machine, and before the new orb destroys itself (the Genesis technology is flawed – Man should not usurp God). As a corrective to faults of recklessness in a Starship captain (he is reprimanded twice for lack of prudence), Kirk’s son is killed on the new planet he made. Upon its release in 1984, the film was a success with cinema-goers, but critics regretted the over-reverential tone and slow-paced direction.

In 1986, a return to something of the old TV series’ humour was attempted in The Voyage Home, the best of the six films, in my opinion. Meyer and Bennett collaborated on the script, an intriguing warning about Man’s lack of care for wildlife. Lack of prudent management of the sea has led to whales becoming extinct, just when a huge space probe is sending violent radio emissions in a bid to contact whales. As there is no reply, the emissions cause more and more atmospheric, marine and electrical disturbances. Kirk, Spock, Scott, McCoy and Co (in a stolen Klingon bird-of-prey ship from the previous storyline) are sent back to 1986, to San Francisco, to capture two whales to transport to the future. What seems a dotty premise is carried through with effortless humour, style and conviction. The interplay of character is spot-on, Nimoy’s direction is crisp, and there are many wonderful scenes of interaction between modern-day America and the Enterprise crew. It is the Star Trek movie I would recommend to the non-Trekkie. Needless to say, the prudent care of our heroes ensures Earth’s survival – and acts as a trenchant reminder of our responsibilities now.

By 1989, the crew of what had been a ‘60s TV hit was looking increasingly elderly, but this did not hinder the making of two final films. The Final Frontier was the most overtly religious instalment of the franchise yet; critic Peter Hansenberg saw the film as being part of an ‘80s tendency to couple sci-fi and religion. Director William Shatner (Kirk) liked the idea of a man seeking The Creator but finding Satan, and then sacrificing himself to save others. The plot revolves around Spock’s half-brother, Sybok, who believes he can locate God. Roddenberry was unhappy that the idea of God was a purely Western one, but the victor is prudence (of course), although Kirk and McCoy are sentenced to imprisonment on the asteroid Rura Penthe. The final part of the epic, 1991’s The Undiscovered Country, sees Kirk losing the hatred he has nurtured for Klingons since the death of his son. Prudence, that most durable of virtues, restores galactic peace, brings spiritual healing and lays to rest the ghosts of the past.

The six original Star Trek films have conviction and a seriousness of approach which endows them with loftiness, but what makes us believe that a close-knit bunch of friends knew and worked with each other is because they really did – for nearly 30 years (not without rows). The virtues of their fictional creations were many: love, dedication, fortitude; but what ennobled and sustained them was prudent care for their mission and for each other.

Simon Potter teaches at Wimbledon College where he was Head of English from 1981 – 2002. He currently produces the school’s plays part-time. He is a member of The Society of Authors and has published 8 titles on Shakespeare and poetry, a novel, a technical work on motorcycles, a book about Wimbledon College, poetry for various anthologies, and technical and literary articles.

![]() Thinking Faith’s review of 2009’s Star Trek

Thinking Faith’s review of 2009’s Star Trek

![]() Thinking Faith’s review of Star Trek: Into Darkness

Thinking Faith’s review of Star Trek: Into Darkness

‘Virtues on Film’ on Thinking Faith:

The Saving Power of Christian Virtue in The Lord of the Rings by Catherine Hudak Klancer

The Saving Power of Christian Virtue in The Lord of the Rings by Catherine Hudak Klancer

Fortitude in Of Gods and Men by Niall Keenan

Fortitude in Of Gods and Men by Niall Keenan

Faith in High Noon by Karen Eliasen

Faith in High Noon by Karen Eliasen

Justice in A Royal Affair by Nathan Koblintz

Justice in A Royal Affair by Nathan Koblintz

Caritas in Quartet by Quentin de la Bédoyère

Caritas in Quartet by Quentin de la Bédoyère

Hope in Life is Beautiful by Frances Murphy

Hope in Life is Beautiful by Frances Murphy

‘The Seven Deadly Sins on Film’ series on Thinking Faith:

‘The Seven Deadly Sins’ by Nicholas Austin SJ

‘The Seven Deadly Sins’ by Nicholas Austin SJ

‘Envy’ in Amadeus

‘Envy’ in Amadeus

‘Pride’ in The Talented Mr Ripley

‘Pride’ in The Talented Mr Ripley

‘Lust’ in Shame

‘Lust’ in Shame

‘Sloth’ in American Beauty

‘Sloth’ in American Beauty

‘Greed’ in Shallow Grave

‘Greed’ in Shallow Grave

‘Gluttony’ in Super Size Me

‘Gluttony’ in Super Size Me

‘Wrath’ in Shine

‘Wrath’ in Shine