For the month of April the Jesuit 2014 calendar, which commemorates the 200th anniversary of the restoration of the Society of Jesus, focuses on Vicente Cañas, a Spanish Jesuit brother who lived among the indigenous tribes of the Amazon for nearly twenty years. Paul Martin SJ thinks about the life of a man who, ‘through the Spiritual Exercises, found the interior freedom to offer his very self to Christ’.

When I was asked to write these words on Vicente Cañas, the guidelines given were, ‘don’t concentrate on dates, places and events – people can get all of that from Wikipedia. Make it more a personal reflection.’

Well, naturally, before writing I thought I myself had better first check Wikipedia! Following a link from there led me to the Aragon Jesuit Province website where an article (thanks to the wonders of Google Translate) gives even a non-Spanish-speaker a good sense of the ‘dates, places and events’.

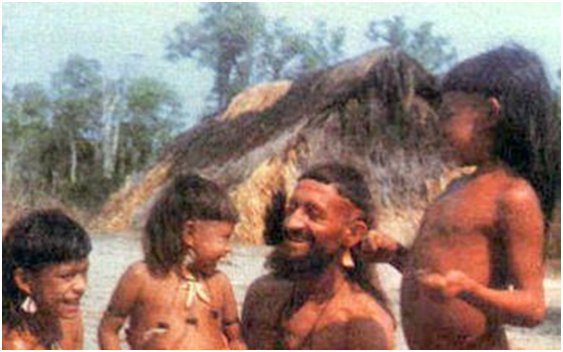

Along with this article there are a number of striking photographs. So, before knowing even a single date, place or event you are caught up into something of the spirituality and mysticism that weave those ‘dates, places and events’ into the unity that was the life of Vicente Cañas –offered with total generosity to God and laid down in love for his friends.

In the first photograph at the beginning of the article, a group of indigenous Amazonian children stand laughing in the company of an adult man. At first glance the adult appears to be another Amerindian – the father of some of the children perhaps? The beads he wears over his bare chest, the large wooden earrings, the hair cut in a clear line high over his ears, the cord tied around his upper arm... each feature in every way identical to the children he is with.

But for those who know indigenous people, one thing is strange and out of place. It is the man’s thick beard – a thing unheard of among the native peoples of the Amazon whose facial hair runs at most to a few wispy strands under the chin. It is the beard that gives this man away as a European.

So who is this European and what is he doing there? The smiles and laughter that he shares with the children are the clue. Here, there is mutual recognition; here, there is understanding; here, there is respect; here, there is encounter.

The children belong to the ‘Enawene-Nawe’, one of over 200 different tribes of indigenous people that live in the Amazon forest. In 1974 they were considered an ‘uncontacted tribe’, their lives untouched by the ‘outside world’. For them, the bearded man is their ‘contact’. He is the face of the ‘other’. How beautiful, therefore, is the smile on this man’s face and the answering laughter from the children? He does not threaten, he does not impose, he neither ridicules nor rejects. He understands, he accepts, he identifies with, he recognises that mysterious bond of shared humanity that unites as equals the forest-dwellers of the Amazon and the sophisticated twentieth-century European.

Sadly, in the 500 years since Columbus set foot in the ‘New World’, contact between Europeans and the indigenous people of the Americas has rarely taken this form. Violence, invasion, domination and death have been, by far, the more usual characteristics of contact. First come the miners looking for gold and diamonds, then the loggers ripping out the lungs of the world for the money to be made from the sale of timber, and behind them, the ranchers who put more value on the price of beef than on the human beings that once occupied the land their cattle now roam. The violence is blatant – even in our twenty-first century, indigenous people are killed and their villages burned to clear them from the lands they occupy. For this reason it is naive to argue that the uncontacted tribes should be ‘left in peace’. Contact is bound to happen. The only question is whether that contact will be made by those driven by greed for profit, or by men and women, like Vicente, who desire that the indigenous people might be recognised and respected as human beings with rights.

Vicente’s first ‘encounter’ with the indigenous world came in 1969 when, as a young Jesuit brother newly arrived in Brazil from Spain, he was called on to form part of a medical team needed to respond to a disaster among a people known as the ‘Beiço de Pau’. A few months before Vicente came to work with these Amerindians they numbered 600; by the time he arrived their numbers had been reduced to a mere 40. In their case, death had come not through violence but through disease, a disease no more mysterious than the common cold; but for a people with no natural resistance, the flu caught from contact with a European proved more deadly than the ‘Black Death’. Vicente was asked to assist the Brazilian government agency FUNI in a campaign to immunise the remnant of survivors and then help them move to a new location.

This experience marked Vicente deeply. It sensitised him to the precarious nature of existence for the indigenous people of the Amazon. Yet, at the same time, it opened his eyes to the strength and wisdom of the indigenous culture. They had a way of life that was perfectly adapted to their environment. They did not need anything from the outside in order to find what was necessary for existence, and indeed to find fulfilment and joy in their lives.

Vicente spent the next five years working with a number of different indigenous groups in the Amazon before beginning the delicate process in 1974 of making first contact with the Enawene-Nawe, and then identifying with them and living among them for over 10 years.

I will depart from my instructions just briefly and highlight one date and event in Vicente’s life. The date is the feast of the Assumption of Our Lady, 15 August 1975 and the event is Vicente’s profession of final vows in the Society of Jesus. Most tellers of Vicente’s story might pass over this date and event as unremarkable but in many ways I think it holds the key for a true understanding of what made it possible for Vicente, as a European, to enter so fully into the way of life of the indigenous people of the Amazon, and what gave that identification its meaning and value.

For priests and brothers alike it is the experience of making the Spiritual Exercises that lies at the heart of Jesuit formation. Before final vows each Jesuit will have made the full ‘thirty day retreat’ twice, once as a novice and again in a final year of formation called ‘tertianship’. Each year, throughout his life, every Jesuit renews this key experience in a shorter, eight-day retreat.

The Exercises are an experience of personal encounter – the direct encounter between the one making the Exercises and the Creator of all that exists, made possible through the incarnation of God in Jesus Christ, ‘who, though he was in the form of God, did not regard equality with God as something to be grasped. But rather, he emptied himself, taking the form of a slave, being born in human likeness.’ (Phil 2:6 ff)

A pivotal moment in the Exercises comes in the meditation on the ‘Two Standards’. Here, the one who is making the Exercises is invited to recognise the ways in which he or she is being tricked into building a false sense of identity out of the riches and honours that he or she has come to possess. We equate our success in life with our possession of ‘status symbols’. These need not be the crass material objects – the large house, the fancy car, the diamond ring, the Rolex watch – that seem so important to ‘worldly’ people. The academic who thirsts for recognition of his work or even the philanthropist who prides herself on the number of hospitals she has founded are still being driven by a false spirit. Our true identity comes from recognising ourselves to be children of God and that everything we have comes to us as gift. Paradoxically it is in letting go of the things the world tells us are indispensible that we come to know who we truly are.

Because Vicente found his sense of identity in his encounter with Christ in the Exercises, he was able to let go of all that would normally define a European man and so enter fully into the culture and way of life of an Amerindian tribe. He did not observe them from outside, recording and analysing their culture for anthropological research. He became one with them, taking part in their daily chores of farming and fishing but also in the religious rituals that gave a sense of meaning and purpose to these activities. He did not come to ‘convert’ them, to impose his Western world view. Vicente desired to learn to see the world as the Enawene-Nawe saw it.

Seeing the world from the perspective of the indigenous people, he became an outspoken advocate for their land rights. In this way he incurred the hatred of those outsiders who wished to take the Amerindian lands for themselves.

At the centre of the Christian gospel stands the mystery of the Cross. ‘A man can have no greater love than this, that he lay down his life for his friends.’ (Jn 15:13) In the crucifixion of Jesus, God’s unconditional offer of love is revealed. Yet at the same time the crucifixion reveals the human refusal of that offer. The Cross is an invitation to conversion. On which side do we stand: with Christ or with those who crucify him?

Vicente Cañas, through the Spiritual Exercises, found the interior freedom to offer his very self to Christ and to be led to divest himself of his European culture in order to enter fully into the culture of the Enawene-Nawe: ‘and being found in Amerindian form he became humbler yet, even to accepting death... death at the hands of those who would rob the Amerindians of their lands.’

Vicente, the man of peace, the man with whom the children of the forest felt so at home, met his death at the hands of violent men. On 5 April 1987, Vicente sent a radio message to colleagues to let them know he was setting out from the small hut in the forest that he used as a base to go and spend time in the Enawene-Nawe village. This was a journey he was never to make. On 16 May some of his colleagues happened to be visiting his hut. They saw the boat in which he should have travelled to the village, loaded as if for a journey but half submerged. On entering the hut they found clear signs of a struggle and Vicente’s dead body with stab wounds to the stomach. Probably he had been killed on 6 April.

It is the gap of over one month from his death to the discovery of his body that is perhaps the most moving part of Vicente’s story. His colleagues found nothing strange in the fact that he had not made any radio contact. Their visit to his base was not motivated by anxiety to know where he was. It was the nature of his life with the indigenous people that he could go for months without having contact with the ‘outside’ world. In the eyes of that world, he lived an ‘insignificant life’ and he died unnoticed. Yet, to the eyes of faith, Vicente’s life and death take on the profound significance of participation in the mystery of Christ. They become a proclamation of the gospel with an eloquence unequalled by the finest theologians, since, as St Ignatius states, ‘love expresses itself more clearly in deeds than in words’.

Our world has become saturated by words. Perhaps it is good, therefore, to finish this reflection with another image: the photograph of Vicente and the Amerindian boy on the calendar. Vicente’s death is an invitation for us all to concern ourselves with how the child might find ‘life – and life in all its fullness.’

Paul Martin SJ

Jesuit 2014 Calendar: http://calendar2014.jesuit.org.uk/calendar2014/calendar