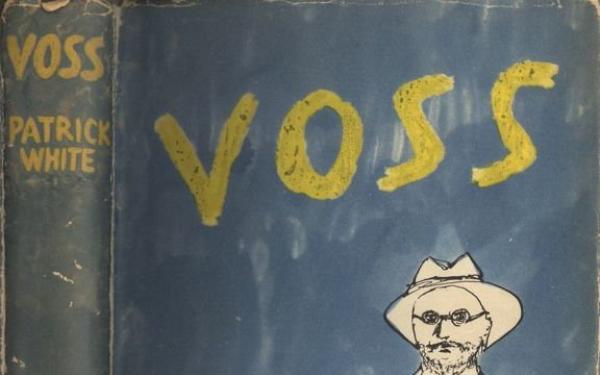

The 1973 Nobel Prize for Literature was awarded to Australian author Patrick White for his ‘epic and psychological narrative art’. Karen Eliasen recently rediscovered one of his novels and was captivated by the prose even as she read it for the second time. After reading her thoughts on a classic that explores identity and faith in the most imaginative and biblical of ways, you will be convinced that you really must read Voss.

Last year, 2012, marked the centenary of the birth of the Australian writer Patrick White, a fact I noted with piqued interest because the name stirred memories of youthful reading habits. Giving in to a fit of nostalgia for long, complex, well-paced and beautifully written fiction, I recently found myself re-reading White’s 1957 historical novel Voss and I found myself as gripped as I was when I first read it some forty years ago. The Nobel Committee for Literature, which granted White its prize in 1973, described his writing as ‘epic and psychological narrative art which introduced a new continent into literature’. This is certainly true of Voss. The novel is epic in its depiction of a doomed 1840s expedition into the great and forbidding Australian interior led by a German explorer, Voss; and it is psychological in its characterisation of the mutual obsession that develops between Voss and a young woman, Laura, whose acquaintance he makes shortly before setting out. On my first youthful reading, keen as I was then on both wilderness survival stories and Jungian romance, I gulped down the surface aspects of these two themes with plot-sensitive curiosity: so what happened next as the motley little expedition trekked across the desert and the mules started keeling over from starvation and black natives with spears appeared on the horizon? And anyway, were these two barely-known-to-each-other Victorian lovers, dialoguing intensely but strictly imaginatively across huge geographical distances, ever going to actually hitch up in the flesh? In the novel, exploration of a harsh, life-threatening wilderness and exploration of a gendered imaginative obsession are narratively interwoven in such a way as to make the two kinds of exploration appear inseparable if not indistinguishable. Both seemed to the young me wonderful adventures, and the novel, I greatly appreciated then, was not lacking in page-turner qualities.

On my recent second reading, I was delighted to find myself again under this same page-turner spell, but also to discover that what had gripped me the first time round was only the tip of the iceberg of what this haunting (and often brutal) novel has to offer. For wilderness and romance adventures are not ends in themselves; rather, White’s novel offers these as a context for a much more solemn exploration of the nature of identity and faith. Voss is indeed an old-fashioned epic, but it is an epic in the form of a beautifully crafted classic that comments questioningly, even subversively, not just on Australian colonial identity but on the broader question of the modern Western self in search of understanding of itself. As the novel’s hero, Voss is conscious of seeking some insight about himself, about who he is and what motivates his behaviour. As he moves deeper into the wilderness interior he at the same time moves deeper into imaginative conversations with Laura. Both the geographical movements and the dialogical movements become more and more pared down to unadorned essentials as the novel progresses. White depicts this pared-down, seeking self as masculine, and further depicts the seeking process as the masculine self moving towards some feminine aspect embedded inside itself. Voss, reeling in the desert, refers to Laura as, ‘this woman who was locked inside him permanently.’ And Laura in a letter to Voss suggests how women might function in men’s psyches: ‘It is the woman who unmakes men to make saints.’ In this psychological narrative, scenes shift in regular rhythm between a beautiful but bleak Australian wilderness, through which a lost, exhausted and increasingly clueless Voss wanders; and a civilised but suffocating urban Sydney society, through which a misfitting, independent and increasingly understanding Laura navigates.

Throughout the novel, these two explorers of outer and inner landscapes, a man and a woman roused to obsession by each other, remain linked in a kind of telepathic communion. I am not sure how appropriately the term mystical applies here to this imaginative enterprise. At any rate, the novel makes liberal use of explicit Christian God-language – something which surprised me as I came across it on this second reading. I had simply forgotten it was there, let alone there to such an overwhelming extent. The narrative may be psychological, but it is a narrative told with a clearly articulated religious dimension, a dimension to which in my youth I had been completely deaf. But now … well, now I am a seasoned Old Testament buff, and I feel especially responsive to the novel’s underlying Exodus symbolism: Exodus with its wilderness wanderings of a people seeking to understand its identity and faith; the Exodus, glimpsed in Judaism, that describes a nuptialencounter between a him and a her, between Yahweh and Israel; and above all Exodus as a book sacralising the human yearning to be made into something new. If in White’s novel, desert and city are juxtaposed, and masculine and feminine are juxtaposed, so too are human and divine. And here I read White not so much as a writerly expositor of opinions as a writerly explorer of saint-making, an explorer in the same vein as his own characters. White is not making claims about how things are or should be, but rather he is inviting the reader to explore along with him the possibilities of finding something new in those same things.

So, wilderness and sex and God-stuff all in page after page of rich prose – how much more gripping can a novel get for a modern Christian of thinking faith?

Karen Eliasen works in spirituality at Loyola Hall Jesuit Spirituality Centre, Rainhill.

You really must read…

![]() Angel Pavement by J.B. Priestley, recommended by Simon Potter

Angel Pavement by J.B. Priestley, recommended by Simon Potter

![]() Fredy Neptune by Les Murray, recommended by Nathan Koblintz

Fredy Neptune by Les Murray, recommended by Nathan Koblintz

![]() Tau Zero by Poul Anderson, recommended by David Baird

Tau Zero by Poul Anderson, recommended by David Baird

![]() Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri, recommended by Dennis Recio SJ

Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri, recommended by Dennis Recio SJ

![]() The Secret History by Donna Tartt, recommended by Michael Kirwan SJ

The Secret History by Donna Tartt, recommended by Michael Kirwan SJ

![]() The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoevsky, recommended by Niall Leahy SJ

The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoevsky, recommended by Niall Leahy SJ